From: The MAP HOUSE

MAP OF THE MONTH

The next map featured on our blog records one of the most remarkable archaeological expeditions ever undertaken. Its accomplishments changed the history of the printed word; in fact, these accomplishments are still reverberating throughout the academic world to this day.

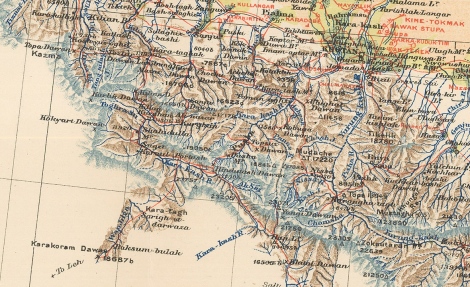

“Map Showing Portions of Chinese Turkestan and Kansu to Illustrate the Explorations of Dr. M. Aurel Stein.” Published for the Royal Geographical Society, 1911.

Sir Marc Aurel Stein was born in 1863 in Pest on the opposite side of the Danube to Buda in Hungary. He was named after Marcus Aurelius, the Roman philosopher Emperor. His family was by no means wealthy but his mother came from a privileged background ensuring that the young boy received a superlative education, an opportunity which he seized with both hands. By the age of twenty, he had gained his doctorate from the University of Tubingen. His passion and subject was the convergence between the history, geography and religion of the Indo-Persian region and his particular specialty were the ancient languages of Persia and India.

Stein was a very affable individual and had gathered a useful group of friends and contacts during his student days. This was something at which he excelled throughout his life and he kept a steady stream of communications with this network no matter where in the world he was travelling at that time.

After he graduated in 1883, he managed to put together a small amount of funds which allowed him to travel to London where he studied ancient Indian coins at the British Museum; it was his first taste of British life and he found it greatly to his liking; so much so that he became a British citizen in 1904.

He did have to go back to Hungary in 1885 to perform his national service. Thankfully for both him and us, he joined the Topographical section of the Austrian army and learnt the skills of surveying and mapmaking; these would become incredibly useful in his later career.

He returned to England and – again due to his contacts – secured an academic position in the Punjab. From that moment onwards, his life began a pattern of constant travel, research, writing and publishing his results and interpretations; followed by numerous public lectures. His thirst for this lifestyle never dimmed and the extent of his travels and exploration is quite extraordinary; from surveying the boundaries of the Eastern Roman Empire in Syria to exploring and recording the archaeology of the legendary Kun-Lun mountain range in Western China. His record keeping was exemplary and as well as his academic records, he wrote and published a collection of popular works on his travels, many of which have also become standard works for the history and archaeology of these regions.

Stein passed away in Kabul in 1943 at age 81, typically planning his next expedition, this time to Central Afghanistan.

Although Stein travelled widely throughout the continent, his most famous expedition was his journey to Central Asia between 1906-8, recorded on this map.

The two great heroes of Stein’s life were Alexander the Great and the 7th century Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, Xuanzang. The latter was a monk who embarked upon a pilgrimage to India both in search of his own enlightenment and to return with documents and records from the country of Buddha’s birth. After seventeen years of travel he returned to China and his account of this extraordinary feat was entitled: “Great Tang Records on the Western Regions.”

Stein was determined to retrace at least some of Xuanzang’s journey and proposed an expedition to study the archaeology of the Silk Road and China’s western border during the Tang Dynasty. He had already reached the legendary city of Ancient Khotan on the Southern Branch of the Silk Road on an earlier journey but this time, the scope of his expedition was far more ambitious and he wanted to travel far further East.

Thankfully, he already had the experience of organizing several important expeditions and had proved he had a prodigious talent for both organization and producing results. This experience, combined with his charm and network of contacts, helped him to secure sponsorship from the British Museum and the Government of India. Once that was in place, the expedition set out in 1906.

As can be seen from the red route on the map, Stein made his way through Leh in Kashmir and then re-visited Ancient Khotan; the map records a mixture of extraordinary geographical detail together with the superimposition of archaeological and ancient sites, again marked in red. This is archetypal Stein, whose topographical accuracy was legendary and remains one of the main reasons why his work is still valid to this day.

Once had had reached Khotan, Stein carried on East to reach his main goal, the Western borders of China which ultimately took him to the site that would change his life.

These old Chinese borders ran close to another ancient Chinese oasis settlement on the Silk Road, Dunhuang. Within a few miles of the oasis, lay a series of caves and temples long associated with Buddhist pilgrims. This complex was known as the Mongao Caves or “The Caves of a Thousand Buddhas.” The complex had long been neglected and housed one self-appointed caretaker, a Daoist monk, Wang Yuanlu, who had recently made a momentous discovery. In 1900, behind a false wall, he had found a cave which housed tens of thousands of ancient documents; these were assumed to be Buddhist, but later study has also found Nestorian Christian, Jewish, Manichean and Daoist texts among the collection. It is not known if Stein was aware of this discovery as he was travelling through the desert but he would certainly have found out about it as soon as he reached Dunhuang.

These old Chinese borders ran close to another ancient Chinese oasis settlement on the Silk Road, Dunhuang. Within a few miles of the oasis, lay a series of caves and temples long associated with Buddhist pilgrims. This complex was known as the Mongao Caves or “The Caves of a Thousand Buddhas.” The complex had long been neglected and housed one self-appointed caretaker, a Daoist monk, Wang Yuanlu, who had recently made a momentous discovery. In 1900, behind a false wall, he had found a cave which housed tens of thousands of ancient documents; these were assumed to be Buddhist, but later study has also found Nestorian Christian, Jewish, Manichean and Daoist texts among the collection. It is not known if Stein was aware of this discovery as he was travelling through the desert but he would certainly have found out about it as soon as he reached Dunhuang.

For an archaeologist, this was the discovery of a lifetime and Stein negotiated the purchase of a part of the collection on behalf of the British Museum and the Government of India.

Stein completed his expedition in 1908 and upon his return the manuscripts were divided between the Indian government offices in Calcutta and the British Museum. Amongst the collection sent to the British Museum was the Diamond Sutra, a printed scroll published in about 860AD, incontrovertible proof that printing was used in China approximately 600 years before its origins in Europe.

As a final note, French, Russian, German and Japanese expeditions reached the Mongao caves soon after Stein and all of them purchased parts of the manuscript collection. In 1914, Stein visited the Caves again and was greeted enthusiastically by Wang Yuanlu, who proudly showed him the improvements he had been able to make with the funds he had raised. These were mainly new and larger facilities to house pilgrims.

Today, the manuscripts purchased by these expeditions are housed in a variety of public libraries and institutions; there is an international co-operative project between all of them which promotes, shares, digitizes and publishes both research and translations of these documents: appropriately, it is named the International Dunhuang Project.

No comments:

Post a Comment