Scythians

Warriors of ancient Siberia 14 September 2017-

14 January 2018

British Museum London

organised with the State Hermitage St Petersburg Russia

2,500 years ago groups of formidable warriors roamed the vast open plains of Siberia. Feared, loathed, admired – but over time forgotten… Until now.

This major exhibition explores the story of the Scythians – nomadic tribes and masters of mounted warfare, who flourished between 900 and 200 BC. Their encounters with the Greeks, Assyrians and Persians were written into history but for centuries all trace of their culture was lost – buried beneath the ice.

Explore their lost world and discover the splendour, the sophistication and the sheer power of the mysterious Scythians.

e 2017 – 14 January 2018

Artist's impression of a Scythian and his horse. Reconstruction by D V Pozdnjakov.

30 May 2017

The Scythians (pronounced ‘SIH-thee-uns’) were a group of ancient tribes of nomadic warriors who originally lived in what is now southern Siberia. Their culture flourished from around 900 BC to around 200 BC, by which time they had extended their influence all over Central Asia – from China to the northern Black Sea.

From September 2017 you can discover these fearsome warriors and their culture in a special exhibition at the British Museum. But before that, swot up on some key facts and impress your friends down the pub with your new-found Scythian knowledge.

1. They were formidable warriors

Gold plaque of a mounted Scythian. Black Sea region, c. 400–350 BC. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin.

Until the 1700s, a lot of what we knew about the Scythians was cobbled together from a range of ancient sources – none of them written by the Scythians themselves as they didn’t ‘do’ writing. So what we had was a collection of accounts written by Greeks, Assyrians and Persians – and they were usually terrified (although often also impressed).

The Greek historian Herodotus, in his Histories (Book 4, 5th century BC), wrote: ‘None who attacks them can escape, and none can catch them if they desire not to be found.’ Assyrian inscriptions from the 7th century BC also refer to fighting Scythians, with one mentioning a peace treaty secured by marrying off an Assyrian princess to a Scythian king.

When the Scythians weren’t being hide and seek champions, or being fobbed off with foreign princesses, they even developed a powerful new type of bow which was made from different layers of wood and sinew. It was much more powerful than a regular wooden bow, as the different layers increased the forces and energy when the string was released.

Gold sew-on clothing appliqué in the form of two Scythian archers.

In battles, the Scythians would use large numbers of highly mobile archers who could shower hundreds of deadly arrows within a few minutes. As late as the 6th century AD a Byzantine writer described the deadly effect of mounted archers like these: ‘they do not let up at all until they have achieved the complete destruction of their enemies.’ If this were not terrifying enough, several classical writers state that the Scythians dipped their arrows in poison!

Scythian arrow heads. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin.

When the Scythians fought on foot, their weapon of choice was a battle-axe with a long narrow pointed blade (like a narrow pick-axe). This type of fighting was personal and face to face – the weapons’ tell-tale puncture marks have been found on the heads of excavated human remains.

So all in all, pretty fearsome.

2. They were nomads

Scythians with horses under a tree. Gold belt plaque. Siberia, 4th–3rd century BC. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin.

The brilliantly named ‘pseudo-Hippocrates’ wrote that: ‘The Scyths… have no houses but live in wagons. These are very small with four wheels. Others with six wheels are covered with felt; such wagons are employed like houses, in twos or threes and provide shelter from rain and wind … The women and children live in these wagons, but the men always remain on horseback.’

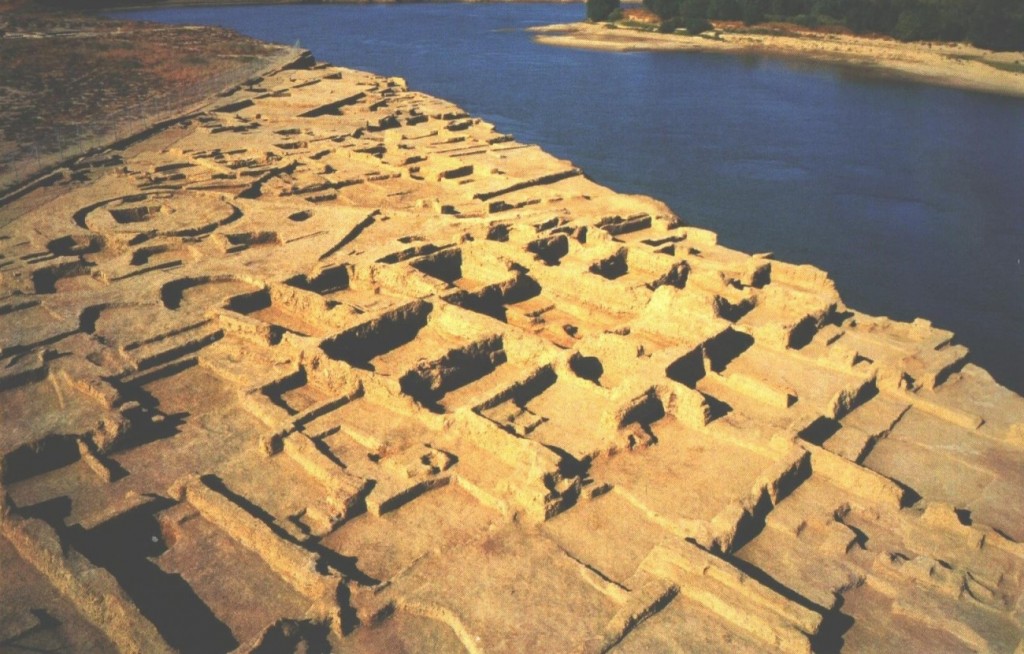

Nomadic peoples tended not to leave a lot behind in terms of cities or literature – what used to be called ‘civilisation’. What we know of the Scythians is largely through excavations of burial mounds (kurgans), and examples of rock art. It is from these remains that we have the archaeological evidence to see if the ancient writers like Herodotus were right – or if they were making it up as they went along.

In fact, our old friend Herodotus thought that the fact they were nomads meant they were extra scary:

‘For when men have no stablished cities or fortresses, but all are house-bearers and mounted archers, living not by tilling the soil but by cattle-rearing and carrying their dwellings on wagons, how should these not be invincible and unapproachable?’ (Histories, Book 4)

Being nomadic, of course, meant having portable possessions that were robust. The objects the Scythians buried with their dead are generally small or lightweight – such as small drinking flasks and wooden bowls. There is no furniture to speak of – the few surviving tables are low and come apart. Thick floor coverings were essential though – sheepskins, felt rugs and even an imported pile carpet have all been found in tombs.

3. They loved their horses

Artist’s impression of a Scythian on a horse. Reconstruction by D V Pozdnjakov.

Siberia is vast. It stretches over eight time zones and borders Europe, China, the Pacific Ocean and Arctic Circle. It is made up of three major ecological zones – icy tundra at the north, dense forest in the central part, and mixed woodland and grassy steppe in the south. This last section forms a wide grassy corridor of rich grazing from Mongolia and China to the Black Sea. It is here that the Scythians began to develop more efficient ways of riding horses which meant they could move bigger herds to new grazing grounds over larger distances.

The Scythians developed horse breeding and riding to a new level. They were accomplished riders and did not use spiked bits or muzzles. Scythian horse gear (saddles, bridles, bits etc) was also highly developed and functional, durable and light. We know this because the large burial mounds contain large numbers of sacrificed horses. These were accompanied by halters, bridles and saddles, and occasionally whips, pouches and shields.

The saddle horses were buried with very elaborate costumes including headgear with griffins or antlers, saddle covers decorated with combat scenes, and long dangling pendants.

Horse headgear. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin.

Scythian horses were well looked after – many were aged between 15 and 20 years when they were put to the grave. Almost all the buried horses were killed in the same manner – a hard blow of a pointed battle-axe to the mid-forehead. Although this is regarded today as a ‘humane’ method, within a society which prized horses, the killing of horses must have made a deep impression.

4. They liked getting drunk and high!

Gold plaques showing Scythians drinking. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin.

Like many cultures, the Scythians drank to excess and got high. Feasting was an important part of Scythian funeral ceremonies – it was also important for social bonding between individuals and tribes. Originally known as ‘milk drinkers’, the Scythians adopted wine consumption from Greeks and Persians. They soon acquired a reputation for excessive drinking of undiluted wine (the Greeks used to mix their wine with water). Greek authors then commented on how the Scythians, like the Persians, liked to drink to excess. You can lead a horse(man) to water (but he’d prefer wine, apparently).

Herodotus also describes how the Scythians had a ritual which involved getting high on hemp in a kind of mobile ‘weed sauna’:

‘They anoint and wash their heads; as for their bodies, they set up three poles leaning together to a point and cover these over with woollen mats; then, in the place so enclosed to the best of their power, they make a pit in the centre beneath the poles and the mats and throw red-hot stones into it… The Scythians then take the seed of this hemp and, creeping under the mats, they throw it on the red-hot stones; and, being so thrown, it smoulders and sends forth so much steam that no Greek vapour-bath could surpass it. The Scythians howl in their joy at the vapour-bath. This serves them instead of bathing, for they never wash their bodies with water.’ (Histories, Book 4)

The Scythians realised the pain relieving effects of marijuana, which no doubt came in useful if they had been in a riding accident or a fierce battle.

5. They were tattooed

Fragment of mummified skin showing a Scythian tattoo. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin.

All the frozen Scythian bodies examined so far from different sites are heavily tattooed. The designs covered the arms, legs and upper torsos. They include fantastic animals locked in combat, rows of birds and simple dots resembling modern acupuncture.

Line drawings of tattoos on a Scythian man.

Other than tattoos, what did the Scythians look like? Some of the women have fair hair and blue eyes but the men are strongly built and have red or dark hair.

6. They liked a bit of bling

Gold torc with turquoise inlays. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin.

Scythian craftsmen were good at casting metal. They worked gold, bronze and iron, using a combination of techniques like casting, forging and inlaying with other materials. None of these required large amounts of equipment and Siberia is rich in metal ores, but it did require skill. There will be many exquisite examples of Scythian metalwork in the exhibition.

7. They mummified their dead

Artist’s impression of a burial mound. Watercolour illustration, 18th century. Archive of the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg.

In the high Altai mountain region near the borders of Russia, Kazakhstan, China and Mongolia, the frozen subsoil has meant that the organic remains of Scythians buried in tombs have been exceptionally well preserved in permafrost.

The Scythians took great effort to preserve the appearance of the dead using a form of mummification. They removed the brain matter through holes cut in the head, sliced the bodies and removed as much soft tissue as possible before replacing both with dry grass and sewing up the skin.

Wooden coffin. Late 4th–early 3rd century BC. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin.

As already noted, nomads do not leave many traces, but when the Scythians buried their dead they took care to equip the corpse with the essentials they thought they needed for the perpetual rides of the afterlife. They usually dug a deep hole and built a wooden structure at the bottom. For important people these resembled log cabins that were lined and floored with dark felt – the roofs were covered with layers of larch, birch bark and moss. Within the tomb chamber, the body was placed in a log trunk coffin, accompanied by some of their prized possessions and other objects. Outside the tomb chamber but still inside the grave shaft, they placed slaughtered horses, facing east.

WOAH! That’s enough for now…

Although Scythian culture remains relatively unknown, new discoveries are happening all the time. Stay tuned to the blog and our other social media channels to find out more about these fascinating nomadic warriors, and book your tickets now to see their culture on display in our special exhibition.

The BP exhibition Scythians: warriors of ancient Siberia is on at the British Museum from 14 September 2017 to 14 January 2018. Supported by BP.

Find out more about some of the key objects on display in this blog post.