Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood by Justin Marozzi, review: 'alive to nuance'

A gripping new history portrays Baghdad as a city of splendour – until the 20th century brought violence on a new scale

Baghdad’s legendary caliph Harun al-Rashid ruled the capital of the Islamic world between 786 and 809. Arab historians would later eulogise “the splendour and riches of his reign”, while storytellers immortalised him in the Arabian Nights as the caliph who roamed among his people. Harun patronised Islamic and Greek learning, and surrounded himself with musicians, philosophers and scientists. Today many Baghdadis wistfully recall Harun’s Golden Age.

But not everyone recalls him so fondly. Like many of Baghdad’s strongmen since the city was founded in 762, Harun plotted against anyone who rivalled him. His vizier Jafar belonged to the influential and urbane Barmakid clan. Harun grew jealous of his minister and made him a sly proposal: Jafar could marry the caliph’s sister as long as he did not sleep with her. When the pair drunkenly succumbed to the inevitable, Harun executed Jafar and crushed the Barmakids.

Likewise, Harun poisoned the Shia saint Musa al-Kadhim – a direct descendant of the Prophet – for opposing his Sunni regime. Today al-Kadhim is commemorated in a magnificent shrine in north Baghdad. Over the centuries it has been a focus for clashes between the two sects.

Justin Marozzi’s superb history of Baghdad is fully alive to the nuances of his story. Marozzi is a fine travel writer who has also written a biography of the Mongol tyrant Tamerlane. Here he interweaves testimony from Baghdadis and written sources to create a gripping account. My one caveat is the subtitle – City of Peace, City of Blood is too optimistically balanced. The supposedly peaceful times were marked by fearsome repression – whether enforced by the caliphs, Mongols, Persians, Ottomans, British or, most appallingly, Saddam Hussein.

Still it’s true, though, that few cities have been so comprehensively destroyed by outsiders. In 1258 the Mongol leader Hulagu wrote to the caliph demanding he surrender Baghdad. Reminding the latter of his grandfather Genghis Khan’s awesome reputation, Hulagu threatened to “turn your city, lands and empire into flames”. Faced with defiance, he was as good as his word. The palaces, mosques, colleges, markets and libraries – the jewels of Baghdad’s civilisation – were burnt to the ground. Scholars, scientists and holy men were, in the words of one Arab historian, “slaughtered like sheep”. The final death toll was 200,000 – a massacre, Marozzi coolly notes, “of 20th-century proportions”.

After Tamerlane sacked Baghdad in 1401 the city never recovered its former glories. The Ottomans later took over this “illustrious but troublesome possession”, but the centre of the Islamic world had shifted to Constantinople, and Baghdad was just a backwater with a famous name.

Equally attracted by Baghdad’s romantic past were the British. In 1917, they wrested control of the city from the fading Ottomans and became the latest great power to dominate. Their commander General Maude was, however, keen to assure Baghdadis he was no Hulagu: “Our armies do not come into your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators.” (During its 2003 invasion the US used similar language.) The British installed an Iraqi monarchy but effectively ran the country.

They left an important legacy in the form of the National Museum of Iraq. Gertrude Bell, the diplomat and linguist who played such a key role in the creation of the country, oversaw the collection of priceless ancient objects from the Sumerian and Babylonian eras. When the museum opened in 1923 it allowed monuments to remain in Iraq.

This makes it all the more tragic, then, that, after the British-supported 2003 invasion, the National Museum was left unprotected from looters. 170,000 artefacts were stolen in all, including the Golden Harp of Ur from 2500 BC and the Uruk mask from 3100 BC, one of the oldest sculptures of the human face. In the words of one archaeologist quoted by Marozzi: “You’d have to go back centuries, to the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258, to find looting on this scale.” The US Secretary of State Donald Rumsfeld’s response was less emotional: “Stuff happens.”

The orgy of violence that followed the disastrous 2003 invasion was a direct result of Baghdadis’ pent-up frustration at being ruled by a depraved dictator. Fancying himself a modern caliph, Saddam built grand palaces and ordered poets to write him panegyrics. Any whisper of criticism was swiftly silenced.

Some Baghdadis still prefer the order of Saddam’s era to the random violence that currently haunts its streets. Many Sunnis are unwilling to accept that their domination of the capital is over and that a Shia, Nouri al-Maliki, is the current prime minister. The Isis forces now threatening to strike Baghdad are a lethal combination of Saddam’s old guard and Sunni religious radicals. Al-Maliki, a tinpot sectarian who runs his own death squads, has proved useless at defending his country. Baghdad’s travails may well be far from over.

Baghdad by Justin Marozzi – review

'Once Paradise … now turned to desert.' This splendid history, which takes in invasions and incest, tries to get to the unchanging essence of the Iraqi capital

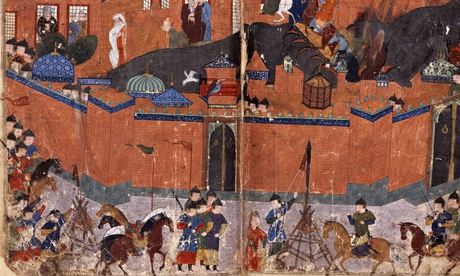

Mongols at the gates of Baghdad in 1258 … from the Jami al-Tawarikh by Rashid al-Din, c 1310. Photograph: Alamy

Of the five historic metropolises of the Middle East – Baghdad, Cairo,Jerusalem, Damascus and Istanbul – it is Baghdad that offers the flimsiest evidence for its own glory. The Iraqi capital – flat, grainy and available for inspection only at risk to life and limb, bisected by a sluggish river of brown water yielding dead bodies, bilharzia and carp – brings for today's visitor a natural tendency to gloom; the sense is that, however glittering the city's achievements may have been, they are now lost. "For only one thing is it now justly famous," declared Robert Byron after flitting through in the 1920s, "a kind of boil which takes nine months to heal, and leaves a scar."

Justin Marozzi, the author of this splendid newhistory of the city, has shown more staying power than his waspish predecessor. He would be a Baghdadi flaneur if the security situation let him – as it is, visits to points of interest are made in body armour. Marozzi has lingered long enough in the city since the 2003 invasion (working on health and education projects) to rally from the near-total absence of a built heritage. He has got to know Baghdad by learning the language, forming friendships and reading the Arab historians of the past.

A special kind of romantic conceit is essential to the kind of book that Marozzi has written and that the other Middle Eastern cities have inspired. (Philip Mansel's Constantinople may be the pick of these city portraits, though Simon Sebag Montefiore's Jerusalem and Max Rodenbeck's Cairo are also very fine.) Writer and reader alike must be convinced that, in spite of the ravages of time, with historic quarters flattened and demographics transformed by massacres, pestilence and flight, the city has not ceased to be what it was when the story began. The aspect changes – even the name – but never the soul.

Marozzi gets to the unchanging soul of his city through diversions from the main historical narrative into more recent life. The opening of a chapter on Harun al-Rashid is a pretext for a long description of a boulevard named after the great Abbasid caliph, from the Ottomans obliterating medieval houses during construction to a coachman, Sheykhan, who plied it in the 1960s. One of Sheykhan's regular passengers was a prostitute for whom he would tout by blowing thunderous raspberries, answered by delighted pedestrians.

The proverb, "Cairo writes, Beirut prints and Baghdad reads", draws Marozzi into the "book-lovers' paradise" of Mutanabbi Street, a "maelstrom of activity with booksellers spreading thousands of new and second-hand titles" ranging from the Qur'an to back issues of Cigar Aficionado – presumably left by the classier sort of American grunt. The nearby Shahbandar coffee house was destroyed in 2007 by a suicide bomb that killed three of the owner's sons, but he subsequently restored the place to use – "a tribute to the resilience of Baghdadis, demonstrated with such tragic regularity over the centuries".

The city was founded by the Abbasid caliph Mansur in 762, set within an auspicious Euclidian circle and enjoying the classic Mesopotamian blessings of an excellent water supply, access to the sea – Basra a short sail down the Tigris – and proximity to the Mediterranean and the uplands of Asia Minor and Iran. Here was an ideal home for an empire that had united east and west for the first time since Alexander the Great.

Goods and people swilled around the empire but it was Baghdad that embodied the Abbasids' ambition, a magnificent new city drawing in a dramatically variegated population of Arabs, Persians and Aramaic-speaking Jews and Christians. "The stage was set," writes Marozzi, "for one of the most extraordinary periods in the history of civilization."

The first two centuries of the Abbasid empire marked nothing less than the absorption by Islam of the taste and knowledge of the world. Envoys sent out by the caliphs brought back Indian mathematical treatises, theories of Iranian statecraft and the models for that affable literary mongrel, The Arabian Nights. Most significant of all were the Hellenic acquisitions – fusty, scholastic Byzantine envoys carried virtually the entire extant corpus of Greek written culture. In time, translation led to Muslim authorship, with the physician and philosopher al-Razi pinpointing the difference between measles and smallpox, and the astronomer al-Khwarizmi popularising the use of numerals. The arts of Baghdad also flourished, Islam fusing with its environment to create a culture of stunning sophistication and beauty, excelling in architecture, textiles, ceramics and metallurgy.

It wasn't all work, work, work. Marozzi diligently chronicles the caliphal downtime, omitting neither incest (a toe-curling story of a man tricked by his mother first into sex with her and, years later, their daughter) nor scatology (an anally retentive dinner guest, a laxative and a prank that backfires). He mines a 10th-century cookery book for gastronomic details – Nabatean chicken was a favourite – and table manners to be observed in the caliph's presence; this is a rich immersion. But the empire's soft centre attracted a rougher gang from the steppe (inspiring the later north African theorist Ibn Khaldun to an influential cyclical theory of government), as the Abbasids were gradually submerged by the Turkic tribes.

The Mongols killed the caliphate in 1258. Hundreds of thousands were slaughtered and the last caliph was starved before being fed a banquet of jewels and trampled to death. Tamerlane's "pilgrimage of destruction" followed a century and a half later, towers of skulls rose around the city and (in the words of an earlier historian) "the land that had once figured as Paradise ... [was] now turned into an arid, treeless desert, across which swept every storm with irresistible force."

Thus, as the Renaissance arrived in Europe, Baghdad was snuffed out as a world city. Contested by the rival Iranians and Ottomans, it was estimated to have a population of only 14,000 by the 1650s. At least it retained something of the old mercantile verve, a mixed population sending Arab horses, Egyptian emeralds and Turkish textiles east to India, and caravans of pilgrims to Arabia further south.

With the exception of Istanbul, the seat of the Ottomans, the great Middle Eastern cities would suffer from provincial sterility in the 18th and 19th centuries, their destinies bound to an empire being torn by national consciousness among its Balkan subjects, and by European powers professing high-minded concern for minority communities such as the Armenians.

Marozzi is good on Baghdad's minorities, particularly the Jews, with their trading outposts in Bombay, Shanghai and London. (Siegfried Sassoon's family came to Britain from Baghdad via India.) There were 80,000 Jews in Baghdad before the first world war, and they sat in the Istanbul parliament – halcyon days before the combined effects of British colonisation, Zionism and Arab nationalism ended the Jewish presence for good. When Marozzi arrived in Baghdad in 2004, the community was seven-strong.

I once had an Arabic teacher in London who was a Baghdadi Armenian. The former head of the Iraq national museum, the admirable Donny George, was an Assyrian. This is the kind of cosmopolitanism that has no place in the new Iraq, where nihilistic groupthink is driving away the minorities that Saddam Hussein – for cynical reasons of his own – wanted to keep. The diversity of Baghdad was once the city's greatness; it has become its flaw.

The crucial line now is between Sunnis and Shias. The feeling among many Sunnis is that the Shias are neither true Muslims nor true Iraqis; rather, they are loyal to the "Magian insects" – as an Iraqi commander described his Iranian Shia foes in the war of the 1980s. Under Saddam, the Sunnis were in control, but now the jackboot is on the other foot, with the ascendant Shias driving many of Baghdad's Sunnis out of their former neighbourhoods and the Sunnis in open (and religiously inspired) rebellion in their provincial strongholds, muttering that it is all a Persian plot.

It wasn't always so. Baghdad's name comes from old Persian, meaning "God gave", and the Abbasid capital was a joint production, with imported Persians constituting an invaluable class of mandarins for their Arab rulers. It is an irony of Baghdad that one of the few monuments to survive from the 500-year Abbasid empire, the Mustansiriya theological school, is in stylistic terms an Iranian building. "Defiance and nostalgia," writes Justin Marozzi, with perhaps more hope than conviction, "are set in every stone."