Proof of a 2,000 kilometre polar trade route in volcanic glass dating back at least 8,000 years

By The Siberian Times reporter

07 March 2019

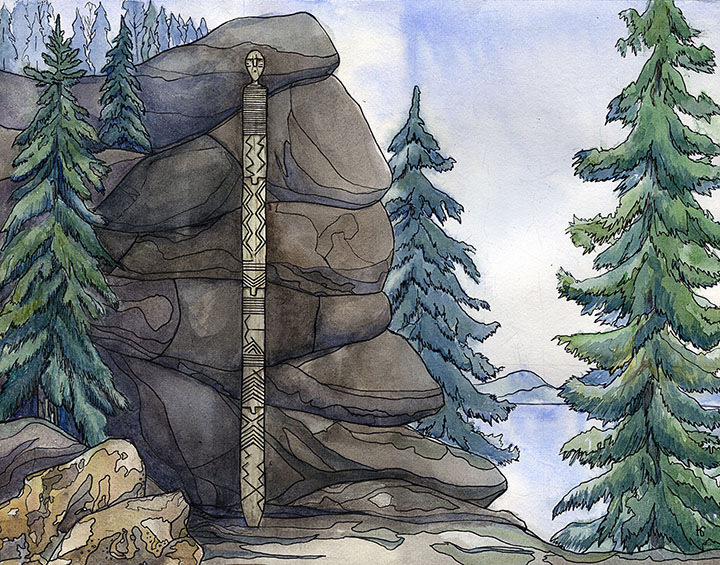

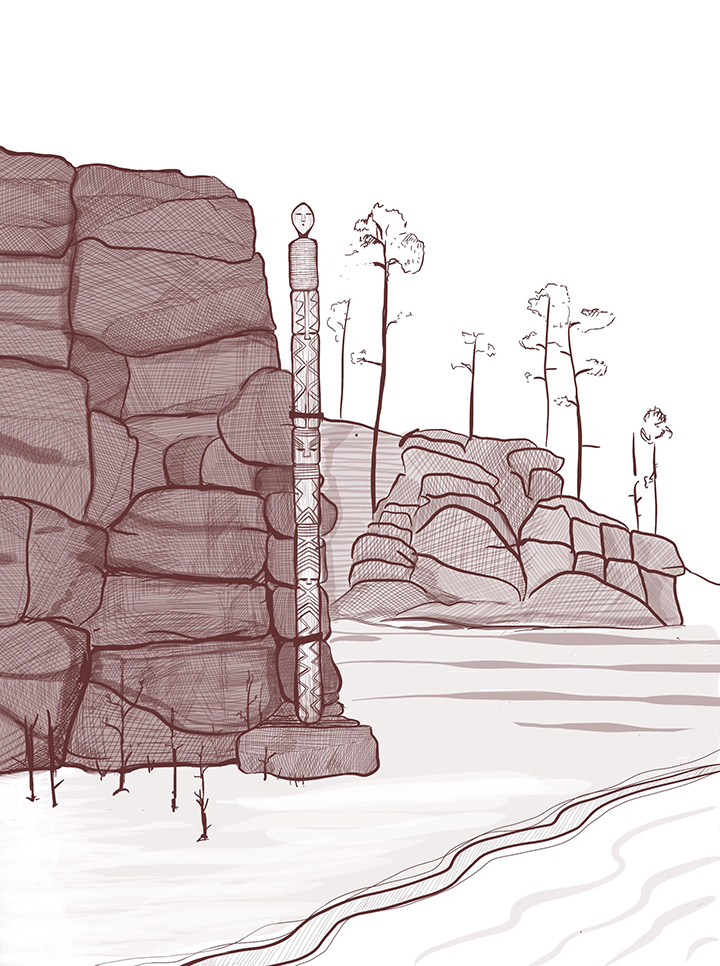

The conclusion is that ancient people used dog sleds to cover these remarkable distances 'at the ends of the earth'. Picture: Alexander Kutsky

But how?

The discovery is breathtaking.

As the crow flies this is a journey of some 1,500 km but as scientist Yaroslav Kuzmin told us ‘the actual distance that obsidian ‘walked’ is at least 2,000 km.

‘This is not just long-range but ultra-long-range transport of raw materials.’

This Great Ice Road was in operation four times as long ago as the famous Silk Road in Central Asia, and it was twice as old as the Egyptian pyramids.

The distance between the exchange points is about 700 km. Picture: Elena Pavlova

The conclusion is that ancient people used dog sleds to cover these remarkable distances 'at the ends of the earth'.

At the time Zhokhov Island - now part of the De Long Islands in the New Siberian archipelago - was connected to the Siberian mainland, and the climate was milder than today.

Yet the distance is still stunning.

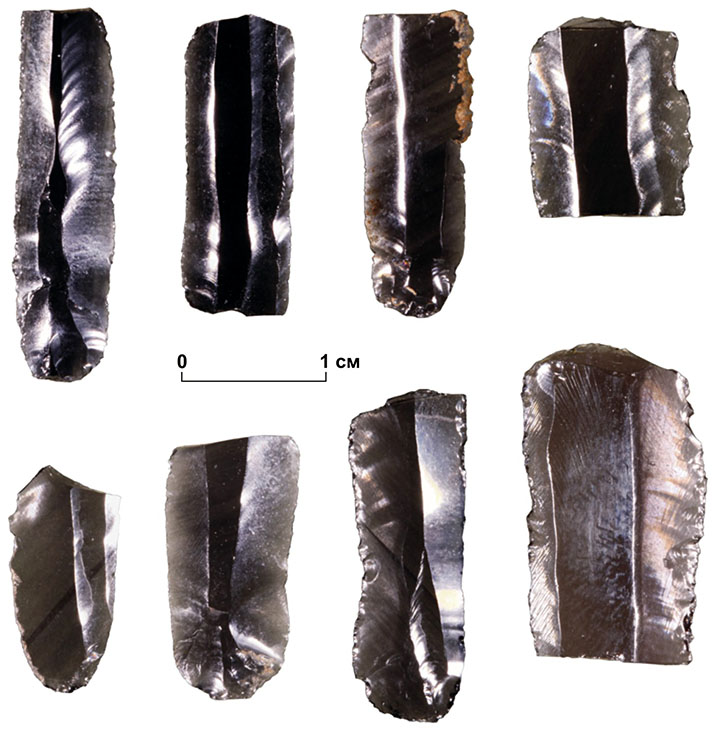

Obsidian was used by ancient people at a famous site on Zhokhov for tools: the black or green volcanic glass, an extrusive igneous rock, was a material of choice.

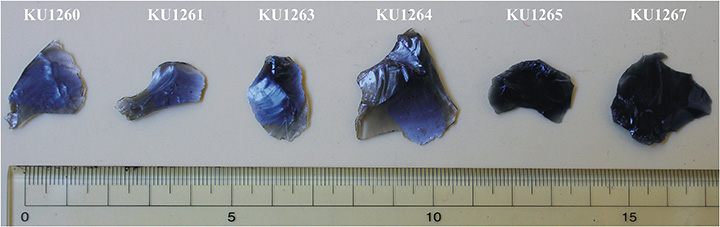

14 obsidian implements from the Zhokhov site were analysed to identify their provenance. Picture: Elena Pavlova

Some 79 tools have been found at the site on the island.

A scientific article in Antiquity reveals how a random 14 of these were analysed to identify their provenance.

They were examined using non-destructive X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to compare the obsidian with known sources in northeastern Siberia.

The geochemistry of the Zhokhov artefacts shows with 90 per cent confidence that it came from a source at Cape Medvezhiy on Lake Krasnoe in Chukotka.

‘The archaeological data from Zhokhov therefore indicate a super-long-distance Mesolithic exchange network,’ conclude the international team of researchers in the Antiquity paper.

Top: Obsidian pebbles found on the shored of the Lake Krasnoye. Bottom: Lake Krasnoye. Pictures: Yaroslav Kuzmin, Evgeny Basov

The scientists doubt the ancient people themselves carried the obsidian all this way.

More likely was an ancient exchange, or trading, system.

The article states: 'In winter time, such a journey required particular skills and technology, such as skiing or the use of snow shoes, both of which were common elsewhere in the Arctic from at least the Early Holocene.

‘While journeys on foot were costly in terms of time, labour and energy, walking allowed for the creation of an exchange network, the scale of which could be expanded significantly by the use of transportation, such as watercraft or animal-powered systems. In both the prehistoric and modern Arctic, the latter is evidenced by sledges pulled by dogs or reindeer.

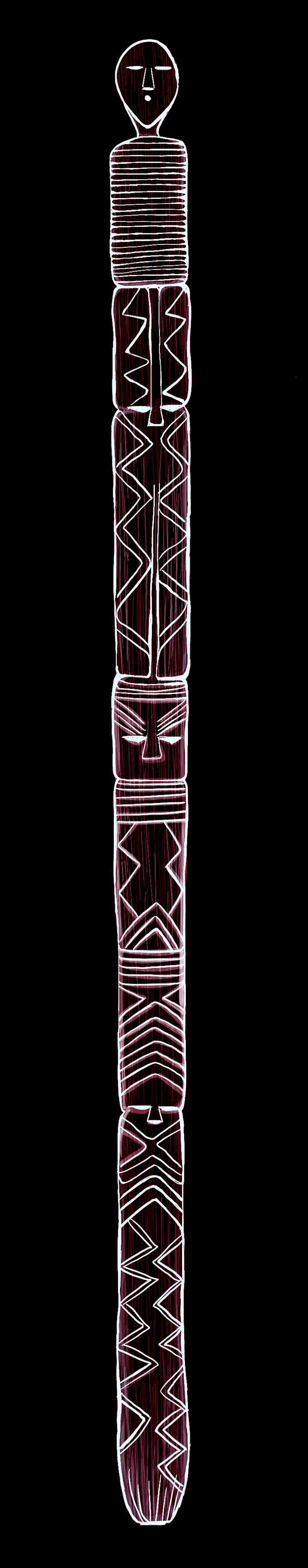

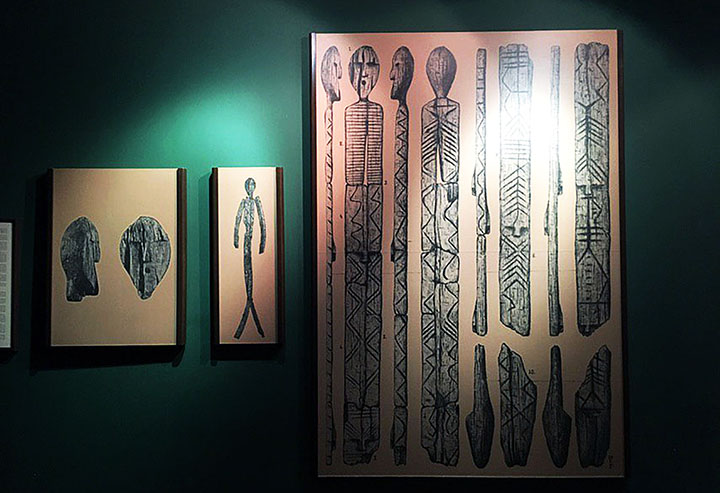

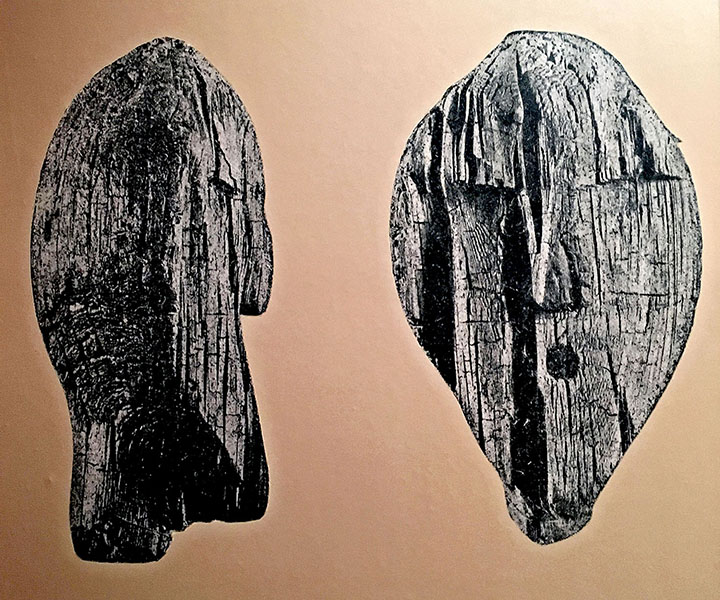

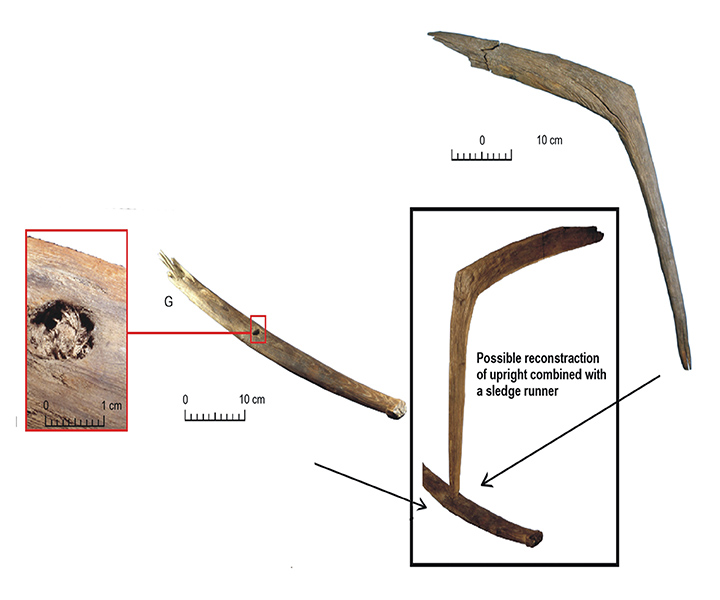

Parts of sledges found on the Zhokhov site. Pictures: Vladimir Pitulko

‘The most suitable season for the use of animals for transport during the occupation of the Zhokhov site would probably have been in early spring (March and April), when snow is still solid and the days are longer than in the winter. Indeed, today, the popular Beringia dog-sled race — a super-long-distance expedition of over 1000 km —normally takes place during this time of the year.

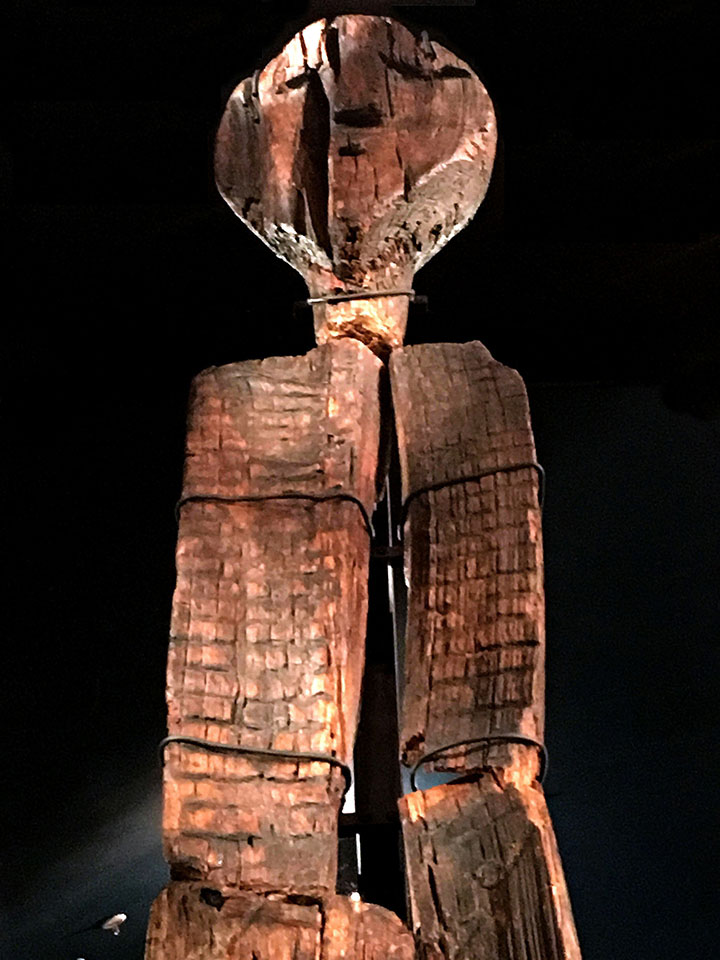

'The Zhokhov site has yielded the world’s oldest evidence for wooden sledge runners and other sledge component parts.

‘Reconstructions from faunal remains of canine body weight and size show that these animals were similar to modern Siberian huskies.

‘Sledge transport formed an important part of the subsistence technology of the Zhokhov site’s inhabitants.

‘Reconstructions from faunal remains of canine body weight and size show that these animals were similar to modern Siberian huskies.‘ Pictures: Vladimir Pitulko, Anikish

It also should be stressed that these people were skilled travellers, who regularly visited today’s New Siberia, Faddeyevskiy and Kotel’nyy Islands to the south and west of the site—as indicated by the presence of raw materials procured from these locations.'

They believe that ‘dog-sled technology, the environment and phenology have remained largely the same in the East Siberian Arctic regions for millennia, regardless of developments such as the introduction of metals, pottery or other innovations.

‘Dog-sled technology undoubtedly played an important part in raw materials exchange networks, as evidenced by the presence of Chukotka obsidian at the Zhokhov site.

‘Although virtually no obsidian has been found in the Early Holocene archaeological record between the Zhokhov site and Chukotka, a connection between these two areas clearly existed by c. 8000 BP.’

Obsidian flakes found on Kolyma river. Pictures: Yaroslav Kuzmin, YSIA

They believe there were staging posts on the exchange route and note that ‘obsidian artefacts have been found in the Malyy Anyuy River basin (in western Chukotka) and in the lower course of the Kolyma River’.

They suggest that ‘it is possible that raw obsidian was transported to the Malyy Anyuy River basin in the Middle–Late Holocene (Neolithic and Bronze Age) as unmodified nodules…

‘The distance between the Lake Krasnoe source and utilisation sites is around 450–500km in a direct line. Fewer obsidian artefacts are found in and around the Kolyma River mouth, which is approximately 850km from the source.’

Excavations at Zhokhov Island. Pictures: Vladimir Pitulko, Elena Pavlova

Kuzmin said: 'It is unlikely that the ancient people made trips to such long distances; most likely there has been an exchange or a primitive trade of obsidian. Sites at the mouth of the Kolyma and, possibly, at the mouth of the Indigirka could serve as intermediate points.

‘In this case, the distance between the exchange points is about 700 km.

’It is quite surmountable in early spring dog sledding.'

The experts believe ‘it is possible that some types of ‘trade hub’ existed in the Siberian Arctic for the exchange of valuable resources, such as stone raw materials, furs and other items’.

It was around 7,800 years ago that the the territory of Zhokhov became detached from the mainland.

They conclude: 'Early Holocene super-long-distance obsidian exchange in the High Arctic is now scientifically demonstrated. Such an exchange system is a remarkable example of a subsistence strategy in use in northern Siberia at that time, if not earlier. The presence of other Mesolithic sites on the north-eastern Siberian Arctic mainland testify — indirectly — to the active contact between human groups across this region.'

The international team of researchers comprised Vladimir Pitulko (St Petersburg), Yaroslav Kuzmin (Novosibirsk), Michael D. Glascock (USA), Elena Pavlova (St Petersburg) and Andrei Grebennikov (Vladivostok).