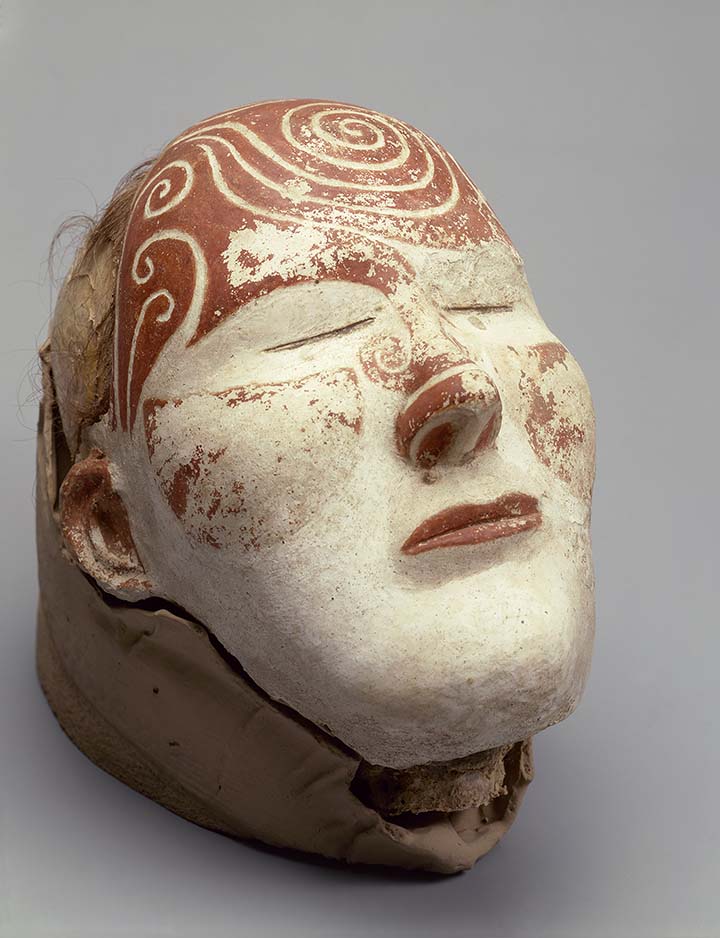

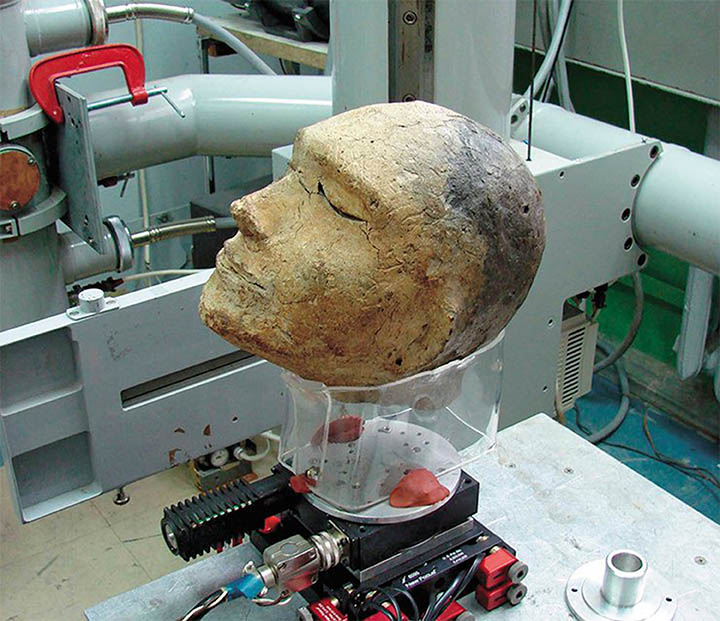

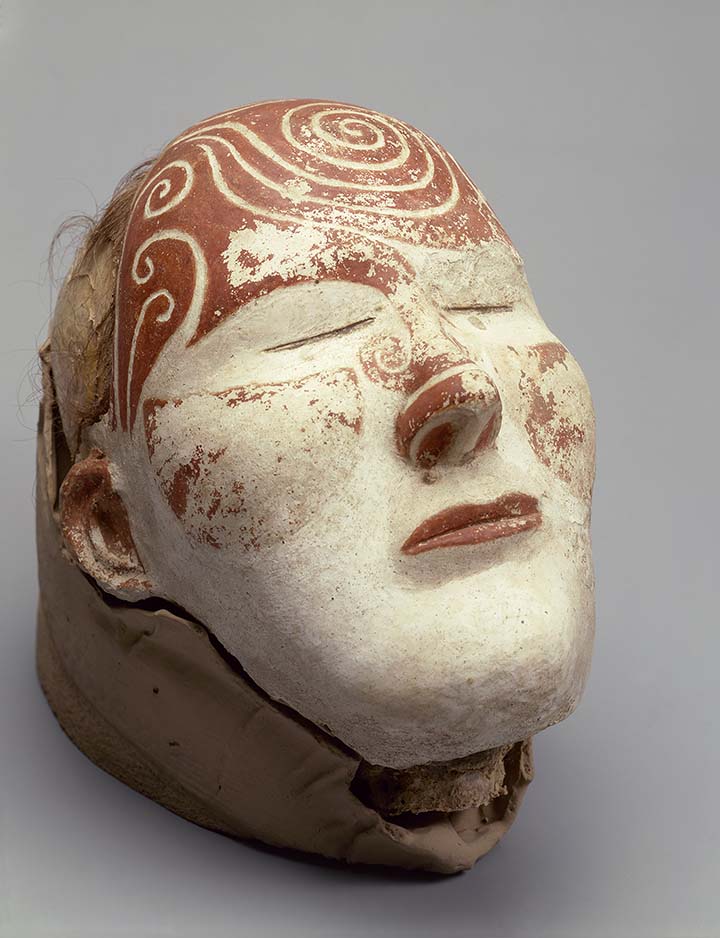

Male Tashtyk mask is kept in the State Hermatage Museum. CT of the mask layer. Pictures: © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin, Pavel Demidov, Darya Bobrova

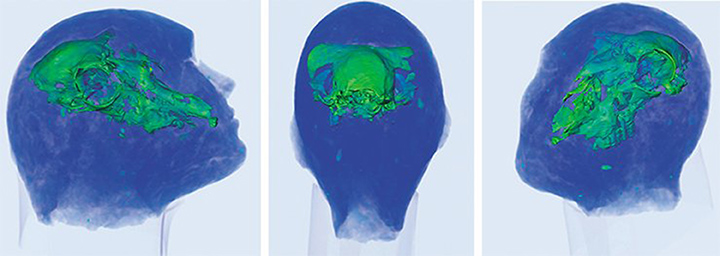

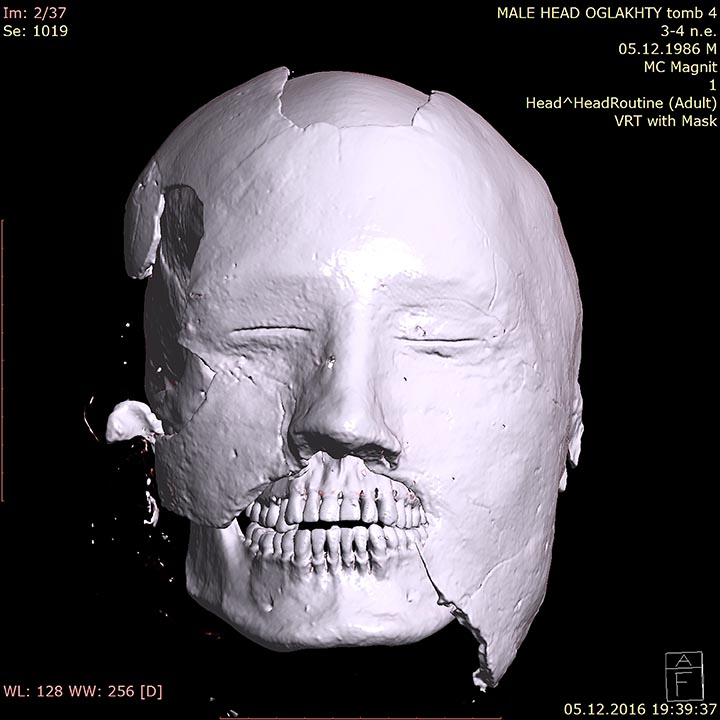

A new CT scan has revealed the face behind his painted gypsum death mask that were all the rage with the ancient Tashtyk people, who were settled cattle-breeders and farmers known for their idiosyncratic burial rituals.

He had brown hair, although the scan gives him a red punk look, and it is believed the pigtail he would have worn had been cut off before his burial.

He is also the only Tashtyk mummy so far found with tattoos.

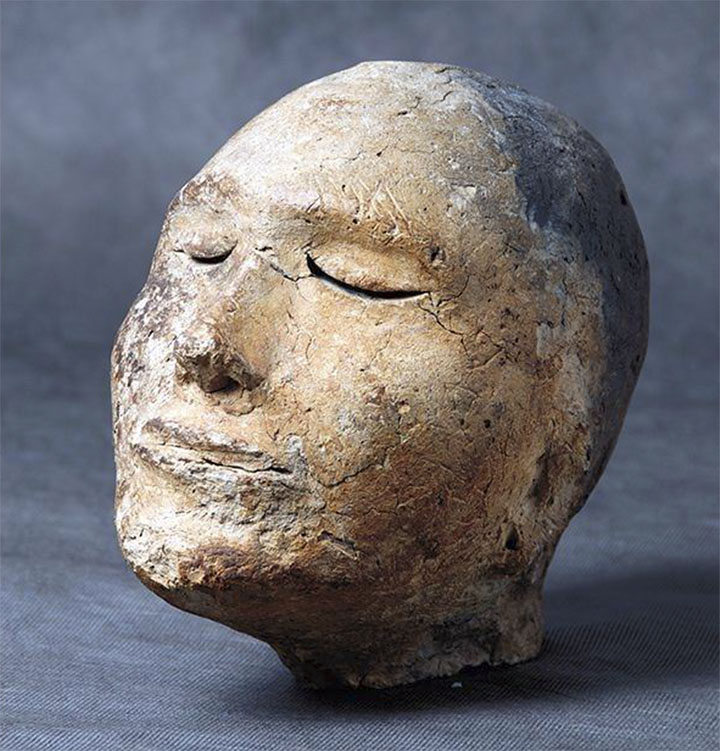

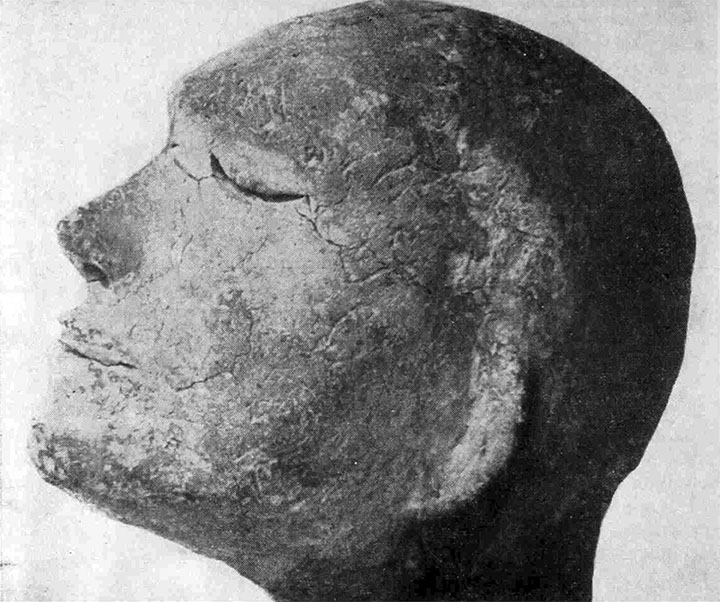

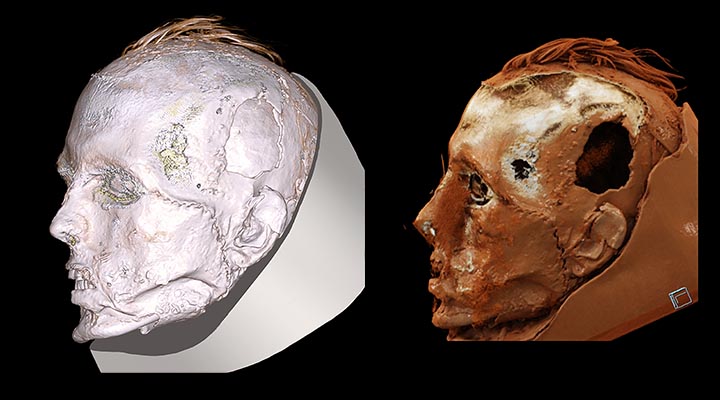

But the most striking and unexpected aspect is a long suture on the side of his face: from the left eye to the ear.

A scar that had been sewn up.

The most striking and unexpected aspect is a long scar on the side of his face: from the left eye to the ear. Picture: The State Hermitage Museum

Archaeologists want more research on this but the current best guess is that this suture was stitched after his death - perhaps to mend his disfigured face after a wound, possibly a fatal blow.

In other words, to improve his looks before his journey to the afterlife.

Final confirmation is still needed that this facial embroidery was postmortem, however.

For now it is not ruled out that this repair job was done at the end of his life.

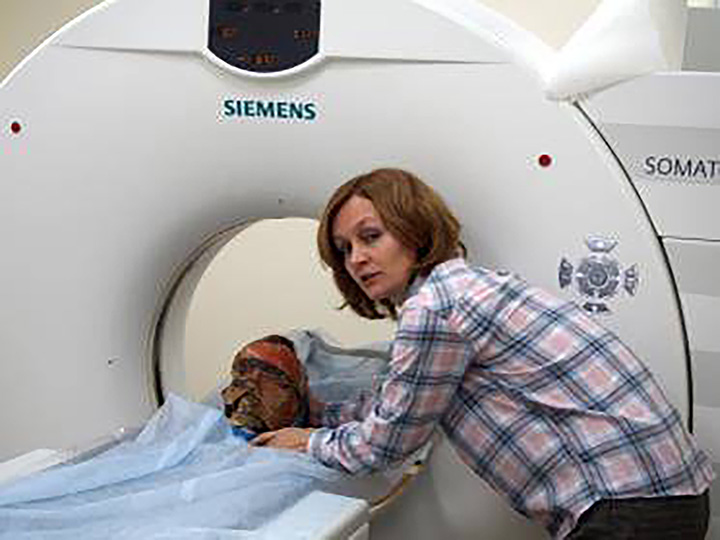

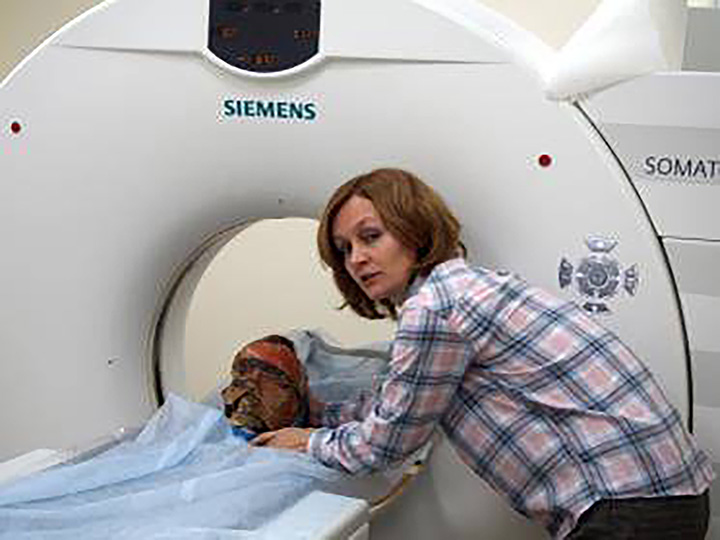

Dr Svetlana Pankova put the male head into the CT scan. Picture: The State Hermitage Museum

Nor was this the only evidence of intervention by ancient surgeons on this Tashtyk man found at the Oglakhty burial ground, and laid to rest in a burial log house.

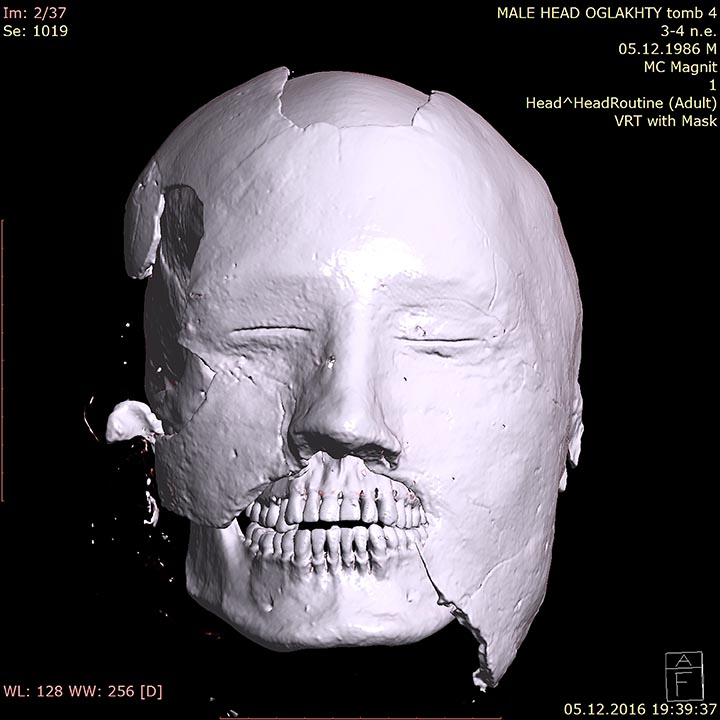

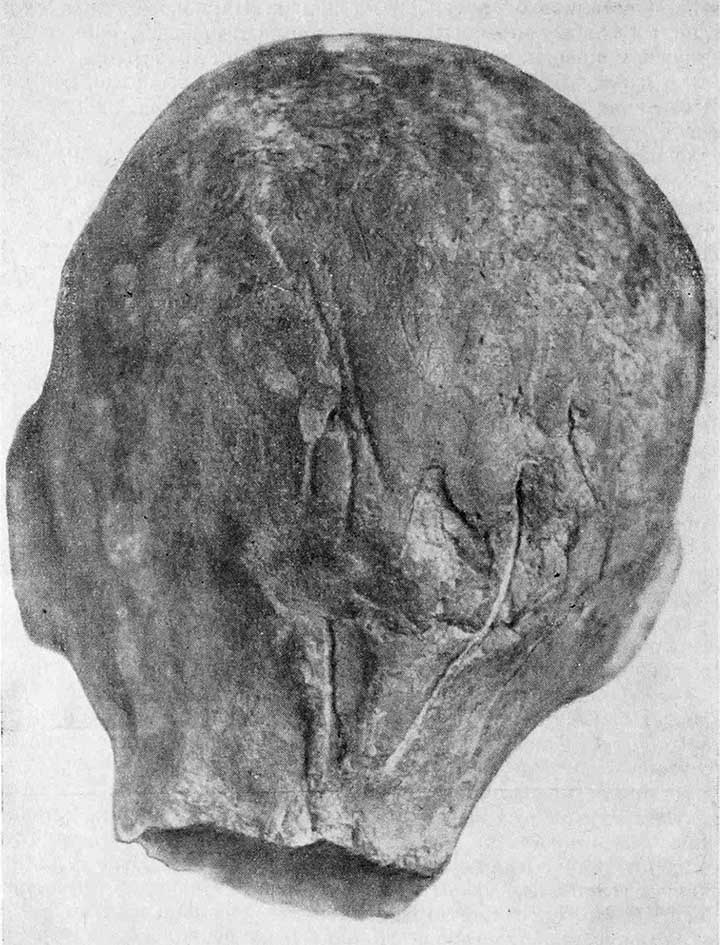

‘His skull was trepanned in the temporal area on the left side,’ explained Dr Svetlana Pankova, curator at the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, and keeper of the Siberian collection of the Department of Archeology.

‘The hole is rather big - 6 by 7 centimetres. It was made postmortem.

‘Expert analysis shows the hole was made by the series of blows with a chisel type or hammer type tool.’

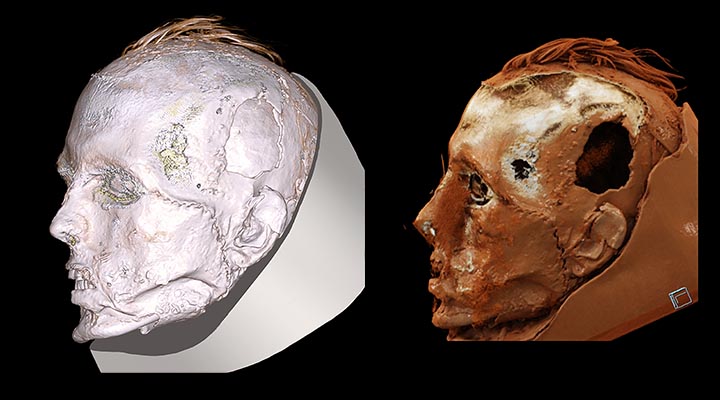

‘His skull was trepanned in the temporal area on the left side.' Pictures: Paul Goodhead, The State Hermitage Museum

Dr Pankova said: ‘We think that it was made to remove the brain during an elaborate burial rite.’

Likewise she thinks the facial scar can be explained in similar fashion.

‘They took all these postmortem rites very seriously, and did not save on this,’ she said.

‘They could not just put a mask on the disfigured face.

‘It would be great to attract an experienced surgeon to research this suture, to get full clarity. Was it postmortem or might it have been been made in his lifetime?

‘Our research is complicated by the fact that we cannot take the mask away from the face (it would cause too much damage) so we must research this stitching using other methods.’

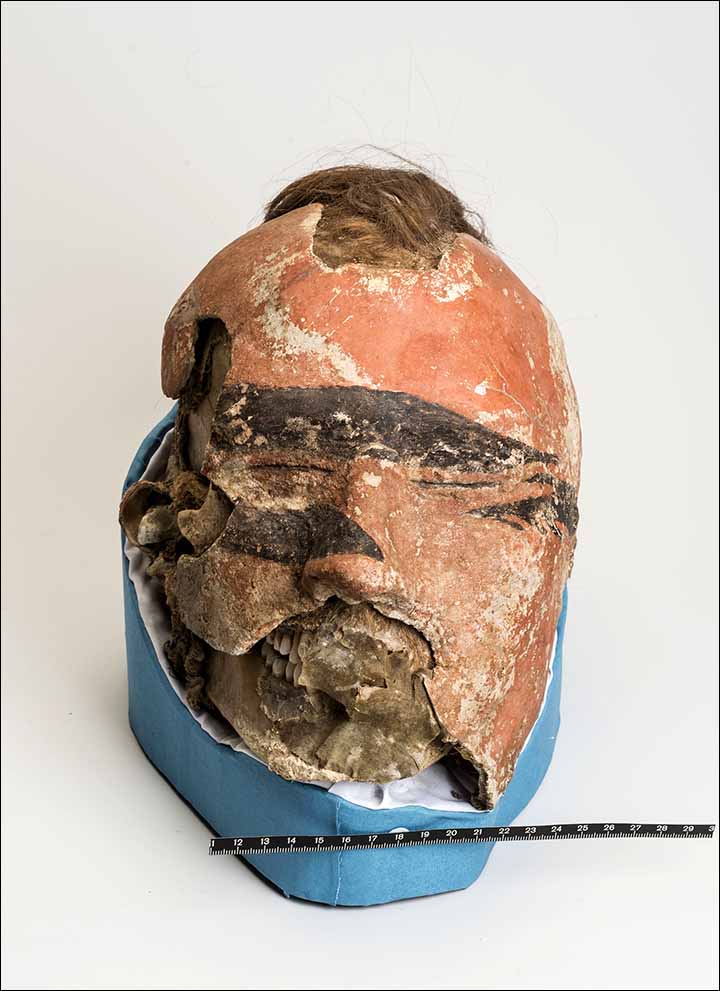

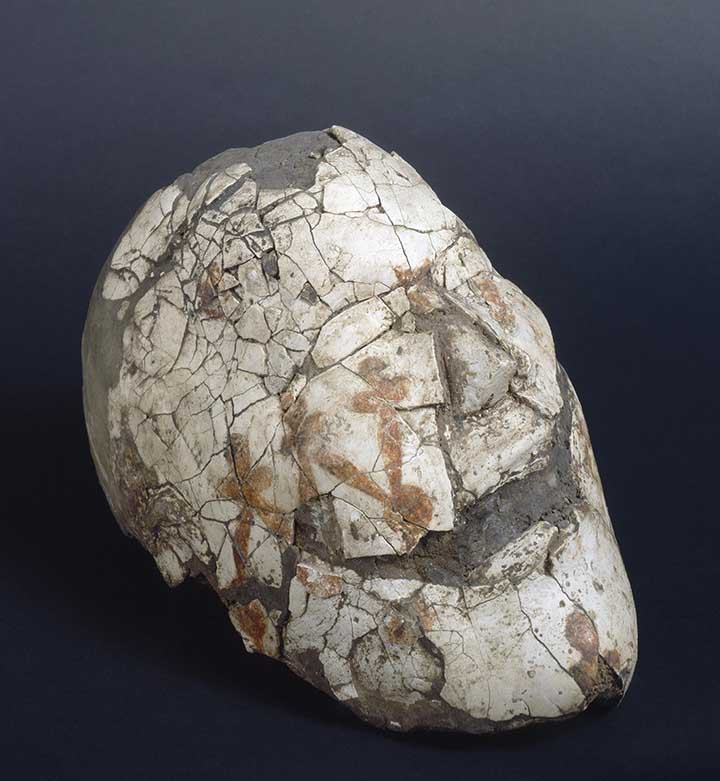

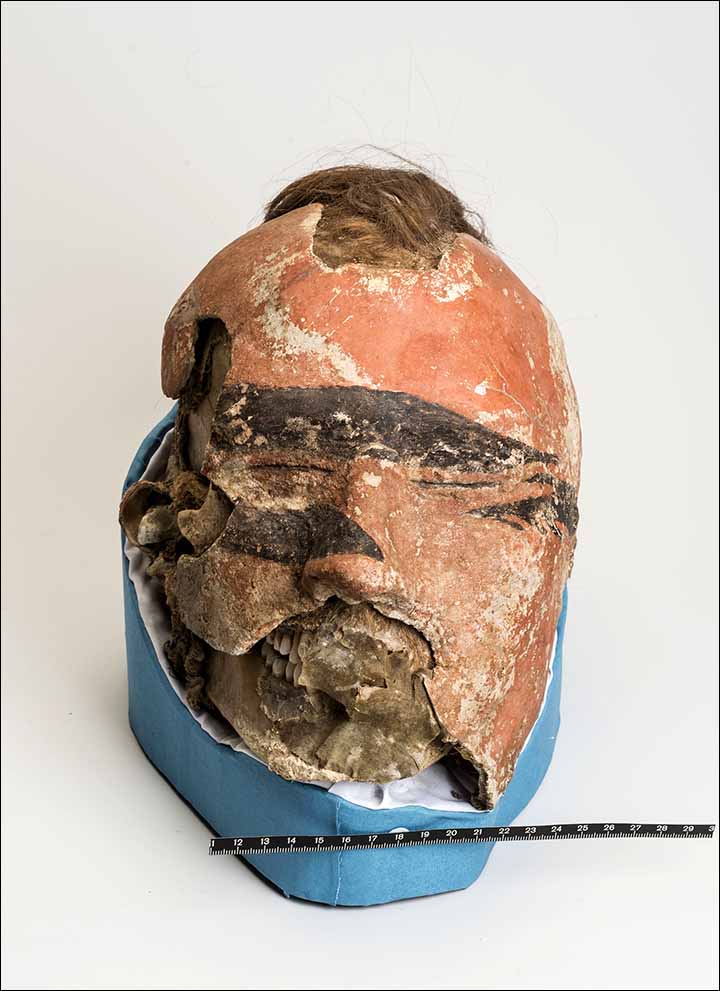

Male mask has black stripes on a red background, plus the lower part of the mask was destroyed and man's teeth can be seen. © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin, Pavel Demidov, Darya Bobrova.

The archadologists were intrigued to finally see the face under the death mask, the painting of which ‘adds some unnecessary emotional impressions’

Dr Pankova said the mask 'has black stripes on a red background, plus the lower part of the mask was somewhat destroyed and man's teeth can be seen.

‘So all together it creates such an aggressive look.’

Yet under the mask ‘there was nothing aggressive in this face.

‘It was the face of a calmly sleeping person.

‘It was the face of calmly sleeping person.' Picture: The State Hermitage Museum

‘The mask was very close in appearance to the real face.

‘For the first time we see the real face of a young man of this time…

‘The computer scan allowed us to see, so to say, three layers - the layer of the mask, the layer of the face without the mask and layer of the skull.’

Svetlana Pankova: ‘I would really like to make CT scan of female mummified head.' © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin, Pavel Demidov.

The face of the woman lying in the same burial chamber - also buried in a fur coat - has not been revealed with a CT scan.

Or anyway not yet.

‘I would really like to make CT scan of female mummified head,’ she said.

‘I am planning to find a clinic which can do this research and decipher it for us.’

For now we do not know who the woman was and how she and the man were related.

Children's fur coat was also found in the grave. © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin, Pavel Demidov.

A child’s skeleton was also found in the same grave.

So, too, were two burial ‘dummies’ - an extraordinary phenomenon akin to stuffed dolls or mannequins.

These may be explained by the merging of two cultures or traditions: one that buried their dead, the other that cremated.

He is also the only Tashtyk mummy so far found with tattoos. Infrared photography. Pictures: The State Hermitage Museum

The dummies appear to represent the remains of those who were cremated.

Yet there is also evidence that men were more usually cremated while women and children were buried.

‘The dummies in full height, kind of mannequins, were made of leather, filled with tightly twisted grass,’ said Dr Pankova.

‘In the chest area there were leather pouches with charred bones remaining from cremations.’

‘The dummies in full height, kind of mannequins, were made of leather, filled with tightly twisted grass.’ © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin, Pavel Demidov

She told The Siberian Times: ‘The mummies, male and female, were dressed in fur coats, and they had masks on their faces.

‘The head of one of the dummies did not preserve.

‘Sadly, probably rodents sneaked in and spoiled it.

‘The second dummy has the face, covered with bright red woollen fabric, with eyes and a nose. On the head was a piece of Chinese silk.’

‘The second dummy has the face, covered with bright red woollen fabric, with eyes and a nose. On the head was a piece of Chinese silk.’ © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin, Pavel Demidov.

The Tashtyk culture existed between the first and seventh centuries AD in the area of so-called Minusinsk Basin of the Yenisei valley.

They were settled cattle breeders and farmers.

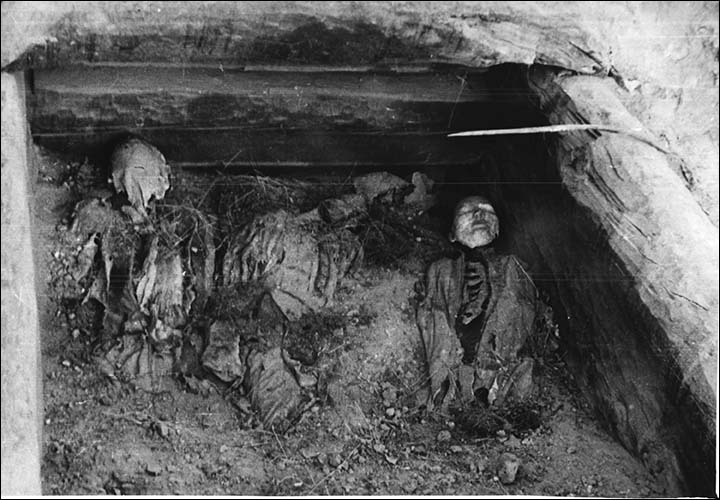

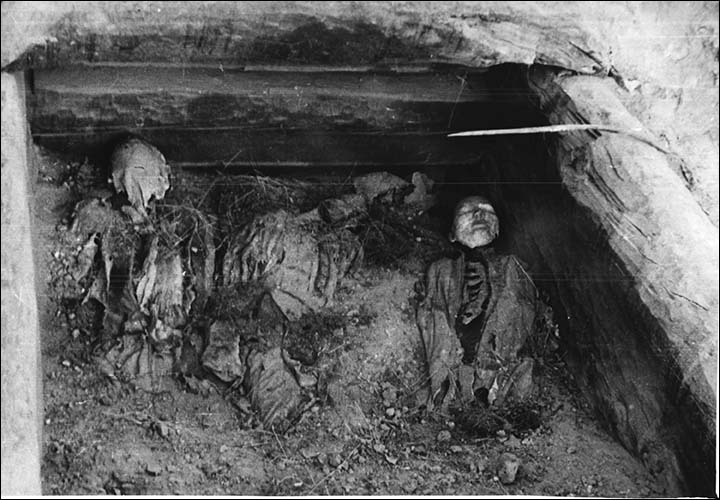

In 1969 Professor Leonid Kyzlasov excavated the Oglakhty burial ground and found this masked man in tomb number four.

‘We made the radiocarbon dating using larch of the log house indicating the third to fourth centuries AD.'

In 1969 Professor Leonid Kyzlasov excavated the Oglakhty burial ground and found this masked man in tomb number four. Pictures: Leonid Kyzlasov, The State Hermitage Museum/ Vladimir Terebenin

The Oglakhty necropolis was originally found in 1902 by a shepherd, who fell into one of the graves, saw the people in a wooden chamber with whitish masks on their faces, got scared, and fled.

His mother-in-law was more fearless, sneaking in and looting some items.

Local official and researcher Alexander Adrianov heard about this and started excavations in 1903, unearthing three graves.