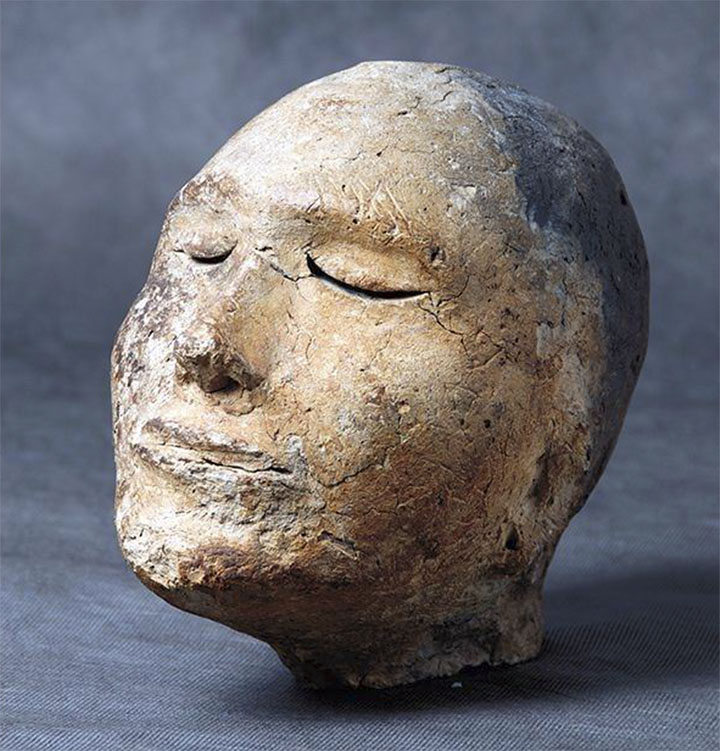

The discovery of the magnificent clay likeness of a young man in the Shestakovsky burial mound No 6 has long intrigued Russian archeologists.

Among cremated people this elegant mask of, perhaps, a handsome warrior immediately stood out as a remarkable find when it was first unearthed in Khakassia in 1968 by Professor Anatoly Martynov.

X-ray technology of the period indicated something was unusual about the bones inside the clay head - but could not reveal more.

‘There are skull bones and a small hollow space, which, however, does not correspond to the inner size of the human skull but is much smaller,’ noted the prescient Martynov in 1971.

Then - and later - opening the clay head was deemed impossible since it would destroy this ancient relic.

Almost four decades later scientists returned to the mystery of this man from the Tagar culture which is known for its elaborate funeral rites, for example the use of large pit-crypts containing some 200 bodies which were set ablaze.

As scientist Dr Elga Vadetskaya had observed, the heads of the dead were covered in clay, moulding a new face on the skull, and often covering the clay face with gypsum.

So the expectation was - in deploying new technology on the man’s death mask - that the bones inside, though small fragments, would be human.

But they were not.

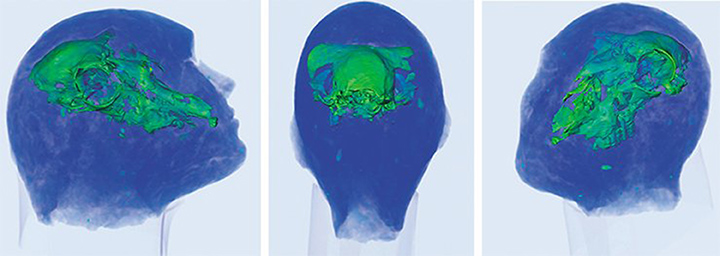

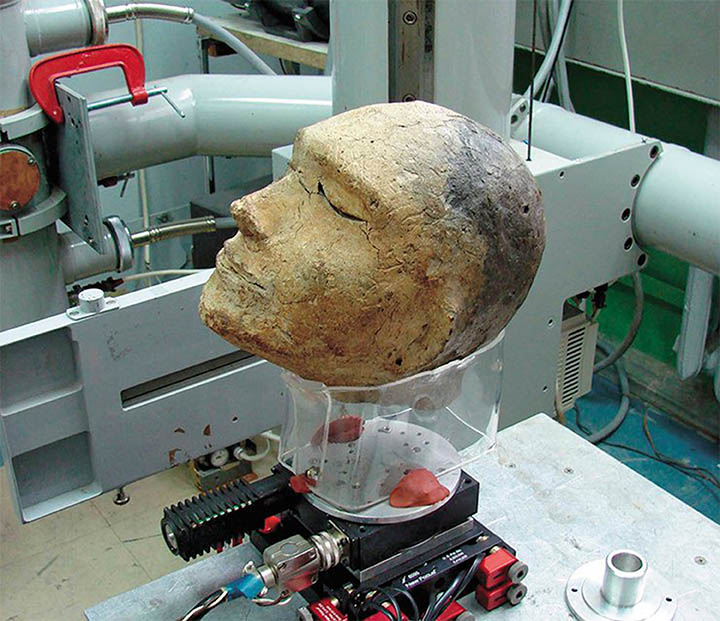

The research was led by Professor Natalya Polosmak, from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, and Dr Konstantin Kuper, of the Institute of Nuclear Physics, both in Novosibirsk, and part of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The man ‘could have got lost in the taiga, drowned, or disappeared in alien lands’. Pictures:

Mikhail Vlasenko

‘I had been working with Natalya Polosmak on other research, and she suggested checking this head because they could not simply look inside - and were puzzled,’ explained Dr Kuper.

‘It was suggested that there was a human skull inside. It was of course quite surprising to see instead a sheep’s skull.’

But…why?

What made these ancient people fill human remains with a ram's remains?

In the

article for the magazine Science First Hand Professor Polosmak offers two options but also acknowledges that ‘as this is the only such case so far, any explanations of this phenomenon will undoubtedly contain, alongside the elements of uniqueness, elements of chance’.

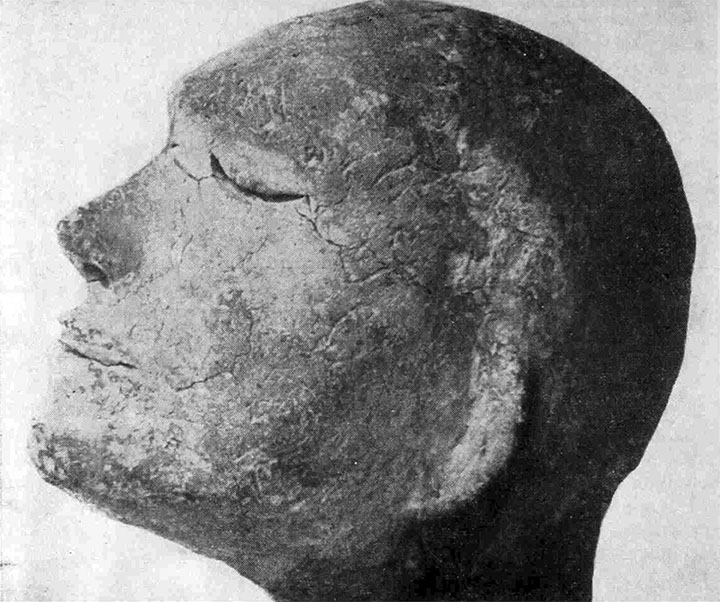

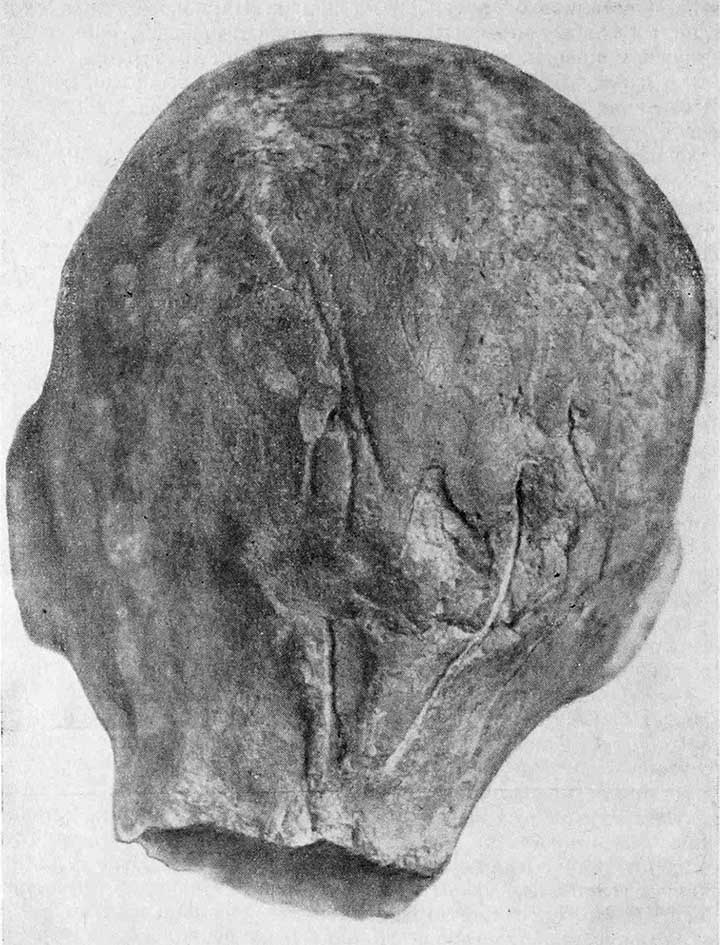

Professor Anatoly Martynov unearthed the head in 1968 in Khakassia. Picture: Kemerovo State University

She believes the Tagar people ‘may have buried in this extraordinary manner a man whose body had not been found’.

She surmises that the man ‘could have got lost in the taiga, drowned, or disappeared in alien lands’.

For this reason he was ‘replaced with his double – the animal in which his soul was embodied’ and in this was sent to the afterlife alongside the remains of his fellow humans.

‘This must have been the only way to ensure the after-death life of a person who had not returned home.

'Archaeologists know a number of such burials, referred to as cenotaphs, which have no human remains but may contain a symbolic replacement. As the latter, an animal could have been used.’

Her other theory for the ‘false burial’ is that it may have been done to give the man ‘a chance to have a fresh start, a new life in a new status.

‘Instead of a living man whose death was staged for some reason, an animal – a sheep in human disguise – was offered.’

One thing is clear: for ancient people the ram had a great significance.

'What does the sheep’s skull hidden under the clay covers depicting a man’s face tell us? What is it, an accident? Or was the animal the main hero of ancient history?

'The latter hypothesis seems justified. A ram (sheep) is among the most worshipped animals of old times. Initially, the Egyptian god Khnum was depicted as a ram (later, as a man with the head of a ram).’

Remains of 200 mummified bodies found in one of the Tagar burial mounds at Belaya Gora. Picture: A. Poselyanin

A third version has been proposed by Dr Vadetskaya in her book 'The Ancient Yenisei Masks from Siberia’ after studying elaborate burial rites of ancient people during this Tesinsk period.

Her work was based on research of other archaeologists but also had fascinating input from forensic experts.

She believed the burial rite had two stages - the first of which was putting the dead body in a ‘stone box’ which then went into a shallow grave or under a pile of stones for several years.

The main goal was partial mummification - the skin and tissues decomposed, but tendons and the spinal cord persisted.

Then the skeleton was taken away intact and was tied by small branches.

Clay head pictured in 1968. Traces of the ropes and sticks, which were used to attach the head to the "funeral doll", visible on the back of the head. Anatoly Martynov

The skull was trepanned and the rest of the brain was removed. Then the skeleton was turned into kind of ‘doll’ - it was wrapped around with grass and sheathed with pieces of leather and birch bark.

Then, according to Dr Vadetskaya, they reconstructed ‘the face’ on the skull.

The nose hole, eyes socket and mouth were filled with clay, then the clay was put onto the skull and the ‘face’ was moulded though without necessarily much facial resemblance to the deceased.

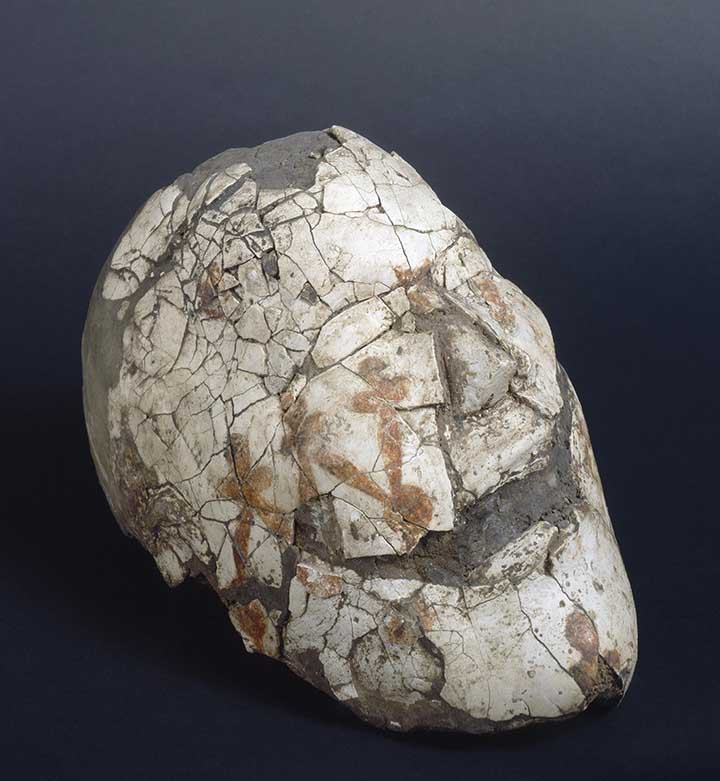

Often this clay face was covered with a thin layer of gypsum and painted with ornaments.

She suspected that these masked mummies went back to their families pending their second, bigger funeral.

This might have been for some years: there is evidence that gypsum was repaired and repainted.

Faces molded on the skulls were often covered with thin gypsum layer painted with ornaments. Pictures: Elga Vadetskaya, The State Hermitage Museum

She wrote: ‘For some mummies the wait was too long. They decomposed, so only the heads were left to be buried.

‘In some cases even the head did not survive. Then they had to recreate the whole image of the deceased one.’

She believed that this was the case with the mysterious human sheep skull.

The ram remains were used to replace the real human skull of this ‘mummy doll’ lost or destroyed during the decades between the two funeral rites.

According to Vadetskaya, a large pit was dug for these ‘Big' funerals.

A log house was erected and covered with birch bark and fabrics.

Many such human remains were put inside, and the log house was with the remains of dead were ignited.

The log house was partly burned down and often the roof collapsed.

The pit-crypt burial was then covered with turf and earth and formed a mound.

In this particular case there were relatively few human remains - no more than 15, yet in others the number could rise into the hundreds.

So - there are three main theories.

Perhaps future scientists will gain access to more elaborate technology to examine this death mask and unlock more secrets about this extraordinary find.