"Did the Buddha visit Khotan?" is a blogpost from Sam van Schaik.

So first a short introduction to Sam van Schaik and than you can rad his article

Did the Buddha visit Khotan?

“The way of the Mahāyāna has been sought by the accomplished in the auspicious places where our Teacher placed his feet, such as the Vajra Seat, the Vulture’s Peak and the Shady Willow Grove of Khotan.”

At the beginning of the 10th century, a chaotic time for Tibet, the scholar Nub Sangyé Yeshé wrote these lines on the sacred places where the Buddha had taught. Two of them are well-known throughout the Buddhist world, but the third is a little more obscure. Is the Buddha really supposed to have visited the Silk Road city of Khotan? According to the Khotanese, he did indeed, and the fact that this was accepted without any need of explanation by an educated Tibetan writer like Sangyé Yeshé shows how far the Khotanese understanding of Buddhism had penetrated into Tibet at this time.

Khotan was the most important kingdom on the southern Silk Route, situated between the Taklamakan desert and the Kunlun mountain range. Two rivers coming down from the mountains brought the water that allowed cultivation of the land, also bringing down jade, the stone prized by the Chinese and the source of much of Khotan’s wealth. Khotan was thus ideally placed to take advantage of east-west trade, becoming in the process open to influences from a variety of cultures. Indigenous legends of Khotan’s early history emphasise both the country’s cultural plurality and its allegiance to Buddhism.

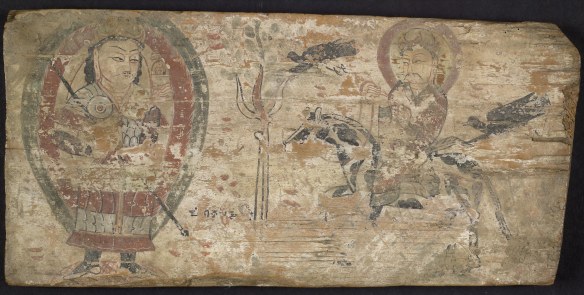

These legends do indeed tell of the Buddha visiting Khotan. In one version, he flies over from Vulture’s Peak to hover above the lake that covered Khotan in ancient times, before descending to rest upon a lotus throne in the middle of the lake. Other legends also brought to Khotan the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara and the protector deity Vaiśravaṇa. Re-imagining themselves as the centre of their religious world became a surprisingly consistent feature of Khotanese culture. When Aurel Stein visited Khotan at the turn of the 20th century, he noted of the Muslim Khotanese: “Pious imagination of a remarkably luxuriant growth has transplanted into the region of Khotan the tombs of the twelve Imāms of orthodox Shiite creed, together with a host of other propagators of the faith whose names are known to local legend only.”

* * *

It may be true, as Stein suggested, that the people of Khotan are a gens religiosissimaparticularly given to pious invention, but a solid Buddhist sangha was resident in Khotan from at least the 3rd century AD. Discoveries of Khotanese manuscripts in archaeological sites in the areas once ruled by the kingdom have shown that the major Mahāyāna sutras were all known in Khotan. These were first written in their original language, then after the 5th century increasingly translated into Khotanese. The Suvarṇaprabhāśa sūtra seems to have been particularly influential, informing the notion of Khotan as a Buddhist realm under the protection of bodhisattvas and divine kings. Alongside this Buddhist material are many examples of Khotan’s literary tradition, stories on Indic themes, like the trials of Rāma, and poems on the ever-popular subjects of nature and love. One unique text, the so-calledBook of Zambasta marries the Khotanese poetic tradition with Buddhist subject matters in a lengthy and wide-ranging survey of Buddhism.

During the seventh to the ninth centuries, the Tibetans were sporadically active Central Asia, fighting the Chinese Tang empire over strategically situated and highly profitable Silk Route oasis cities. The Khotanese first encountered the Tibetans in the seventh century as one among many threatening barbarian armies, enemies of the Buddhist dharma. After a brief period of Tibetan occupation in the late seventh century, Khotan was returned to Chinese rule, to be conquered again by the Tibetans at the end of the eighth century. Then, after the final fall of the Tibetan empire in the middle of the ninth century, Tibetans and Khotanese met in Silk Road towns like Dunhuang in the role of Buddhist teachers and disciples, sharing their knowledge, and translating each other’s religious texts.

And what of the “Shady Willow Grove of Khotan” (li yul lcang ra smug po) mentioned by Sangyé Yeshé? It does appear in a few other later Tibetan sources, including a pilgrims’ guide to the Khadrug temple, which includes a story of how the temple’s statues were obtained from Khotan by the Tibetan army, during the reign of Songtsen Gampo. Later, when the real location of Khotan had largely been forgotten in Tibet, the Shady Willow Grove came to be identified with one of the tantric holy sites known as pīṭha – pilgrimage sites in India associated with parts of the body. The place associated with Khotan was Gṛhadevatā, a problematic site unlocateable in India. On the divine body, Gṛhadevatā represented the anus, a rather ignominious place for the Willow Grove to end up.

* * *

This post is drawn from my paper “Red Faced Barbarians, Benign Despots and Drunken Masters: Khotan as a Mirror to Tibet.” A pre-publication version is now up on the Author page and here.

* * *

Tibetan text

Gnubs Sangs rgyas ye shes’s quote is from Bsam gtan mig sgron, 5–6: rgyu’i theg pa chen po’i lugs kyis kyang sngon ston pas zhabs kyis bcags pa’i rdo rje’i gdan dang/ bya rgod phung po’i ri dang/ li yul lcang ra smug po la stsogs pa bkra shis pa’i gnas dag bya ba grub par byed pas btsal lo/.

I should say that “Shady Willow Grove” is a provisional translation of lcang ra smug po, aslcang ra needn’t always refer to willow trees, and smug po literally means dark red or brown. I’d love any suggestions for alternative translations.

* * *

References

The legend of the Buddha visiting Khotan is in the Prophecy of Khotan (Li yu lung bstan pa); translation and Tibetan in: Ronald E. Emmerick. Tibetan Texts Concerning Khotan. London: Oxford University Press, 1967.

For a review of Khotanese literature, see also his A Guide to the Literature of Khotan. Tokyo: The International Institute for Buddhist Studies, 1992.

Aurel Stein’s quote is from p.140 of M.A. Stein, Ancient Khotan. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907.

On the pilgrim’s guide to Khadrug temple, see pp.62-4 of Per Sørensen and Guntram Hazod, in cooperation with Tsering Gyalbo, Thundering Falcon: An Inquiry into the History and Cult of Khra-`brug, Tibet’s First Buddhist Temple. Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften/Tibetan Academy of Social Sciences of the Autonomous Region Tibet, 2005.

On the identification of the “Shady Willow Grove” with Gṛhadevatā, see pp.95-6 of Toni Huber, The Holy Land Reborn: Pilgrimage and the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

The image is a painted wooden panel from Khotan, possibly representing a Khotanese king (on horseback) and Vairocana.

No comments:

Post a Comment