Smithsonian.com December 30, 2013

Medieval Cone Shaped Princess Hats Were Inspired by Mongol Warrior Women

Image: Hugo van der Goes

Nothing says “princess” like a pointy, cone-shaped hat. From kids’ costumes to medieval paintings, the cone hat—more formally known as a hennin (or henin)—is a sure sign of royalty. But here’s something you might not know about the hat that adorn the heads of pale-skinned ladies: they were actually modeled after the hats of Mongol warrior queens.

The European Henin is modeled directly after the willow-withe and felt Boqta (Ku-Ku) of Mongolian Queens, which could reach over five to seven feet in height.Mongolian women’s boqta also had a special role: because men and women’s clothing were more or less exactly the same in design, appearance and function, reflecting thousands of years of more or less equal rights between the genders, the women’s tall headdresses served to differentiate men and women from a distance.

According to Medieval PoC, Marco Polo brought at least one boghtaq back from his travels, and shortly thereafter there was a sudden boom in popularity of cone-shaped headwear amongst the ladies. Medieval PoC points to the book Secret History of the Mongol Queens, where author Jack Weatherford writes:

The contraption struck many foreign visitors as odd, but the Mongol Empire had enjoyed such prestige that medieval women of Europe imitated it with the hennin, a large cone-shaped headdress that sat towards the back of the head rather than rising straight up from it as among the Mongols. With no good source of peacock feathers, European noblewomen generally substituted gauzy streamers flowing in the wind at the top.

Today, it’s hard to imagine a princess without a cone-shaped hat. But what we think of as the headgear of white Europeans actually began as the headdress of these Mongolian queens.

More from Smithsonian.com:

From: Medievalpoc.org December 28, 2013

The Sa’wkele, The Ku-Ku, The Boqta, The Henin: How the Mongol Occupation of Europe Changed European Women’s Fashion Forever

One of the most immediately recognizable symbols of the European Middle Ages is the towering, often conical or cylindrical, women’s headdresses popular throughout Europe in the 15th century. To this day, the tall, often veil-decorated “Princess Hat” is immediately known even to American children as a sign of feminine stature, nobility, and elegance. Tiny, cheap versions of this hat are sold to women and little girls by the millions at Renaissance Faires, theme parks, costume shops, and carnivals all over the United States. They look something like this:

In just about every American imagination, nothing is more essentially European than the elaborate, gravity-defying tall headdress or henin worn by the noblest women of history. Indeed, the European Henin is synonymous to many Americans as a visual symbol of frail feminity, “Faire Maydens”, milky complexions and delicate white women who must be protected by knights, preferably in shining armor.

(psst. notice people of color in this miniature from Boccaccio’s The Fall of Princes: more on that in later posts)

But what if I told you the heads this historical hat truly belongs on are not only those of women of color, but unrivaled Warrior Queens who ruled a vast empire, went to war with infant sons strapped to their backs, and commanded armies of tens of thousands?

There is something that not even doctorate-holding Western Medievalists and Medieval Fashion experts will tell you, and may not even be aware of: The Henin did not spring out of nothingness to adorn the heads of European noblewomen.

The European Henin is modeled directly after the willow-withe and felt Boqta (Ku-Ku) of Mongolian Queens, which could reach over five to seven feet in height.

Mongolian women’s boqta also had a special role: because men and women’s clothing were more or less exactly the same in design, appearance and function, reflecting thousands of years of more or less equal rights between the genders, the women’s tall headdresses served to differentiate men and women from a distance.

Mongolian equestrian culture influenced fashion as well as martial technology: the headdresses would have been even more impressive on horseback. The higher a woman’s position, the taller, richer, and more elaborately decorated the headdress.

The important cultural role of the headdress is elaborated upon in Weatherford’s Secret History of the Mongol Queens, in this portion about the warrior Queen Maduhai as she prepares to lead her soldiers to war:

The chronicles all agree that she fixed her hair to accommodate her quiver. The hairstyle of noble married women of that era precluded fighting or any other manual endeavor. She removed the headdress of peace and put on her helmet for war.By taking off her queenly headdress, known as the boqta, she removed virtually the only piece of clothing that separated a man from a woman. The boqta ranks as one of the most ostentatious headdresses of history, but it had been highly treasured by noble Mongol women since the founding of the empire.* The head structure of willow branches, covered with green felt, rose in a narrow column three to four feet high, gradually changing from a round base to a square top…The higher the rank, the more elaborate the boqta, and as a queen, Mandhui would have worn a highly elaborate one. A variety of decorative items such as peacock or mallard feathers adorned the top with a loose attachment that kept them upright but allowed them to flutter high above the woman’s head.The contraption struck many foreign visitors as odd**, but the Mongol Empire had enjoyed such prestige that medieval women of Europe imitated it with the hennin, a large cone-shaped headdress that sat towards the back of the head rather than rising straight up from it as among the Mongols. With no good source of peacock feathers, European noblewomen generally substituted gauzy streamers flowing in the wind at the top.

* The ebook preview is truncated. I happen to own the book and have typed out the rest of the passage from hard copy.

** This statement reflects the bias of the author (Weatherford)-forgeign visitors found the boqta overwhelmingly impressive statements of wealth. For primary source description contemporaneous with women in the boqta (c. the 1200s), keep reading below the cut!

FULL HISTORY OF THE BOQTA, MORE PHOTOS AND LINKS BELOW THE CUT!

The first historical reference to the use of the tall headdress by the Mongols occurs in “The Secret History of the Mongols”, penned by a member of the Borjigins, the clan of Chinggis Khan, in the early 13th century – possibly 1228. It concerns Chinggis Khan’s mother at the time she was abandoned by the Tayichi’uts and the rest of the Borjigins following the assasination of her husband by the Tatars, an event that occurred just after 1170:

“Lady Hö’elün, born a woman of wisdom,

raised her little ones, her own children.

Wearing her high hat tightly [on her head],

hoisting her skirts with a sash,

she ran upstream along the Onon’s banks…”In 1221 Chinggis Khan’s Mongol armies conquered Khorezm and its army of Qipchaq mercenaries. At the same moment, the elderly Taoist monk K’iu Ch’ang Ch’un was on his way from China to Samarkand to visit the Great Khan, accompanied by Li Chih-chang and 18 other disciples. After following the Kerulan River towards the Mongolian Altai they encountered a large number of Mongolian nomads living in black carts and white gers:“The men and unmarried girls plait their hair so that it hangs down over their ears. The married women put on their heads a thing made of the bark of trees, two feet high, which they sometimes cover with woollen cloth, or, as the rich used to do, with red silk stuff. This cap is provided with a long tail, which they call a yu-yu, and which resembles a goose or duck. They are always in fear that somebody might inadvertently run against this cap. Therefore, when entering a tent, they are accustomed to go backward, inclining their heads.”

From the numerous Eastern and Western travellers who visited Mongolia and the Qipchaq Steppes in the 13th century we can see how this headdress was transformed into the boghtaq or bughtaq, the most visible symbol of status for aristocratic married Mongol women, local native materials being quickly superseded by more exotic fabrics and jewels from China and Islamic Central Asia. In the very same year the Sung ambassador Chao Hung recorded that the headgear of women belonging to the ruling class consisted of an iron wire frame “about three feet in length, adorned with red and blue brocade or with pearls.” He called the whole headdress a ku-ku. One of the Sung generals, Meng-hung, who had been sent to support the Mongol invasion of the Chin commented that: “The wives of the chiefs wear a cap they call a ku-ku, which is made from a wire about three feet tall and is covered in purple velvet”.

The highly influential Chabi, principal consort of Khubilai Qan, wearing the boghtaq. She died in 1281. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

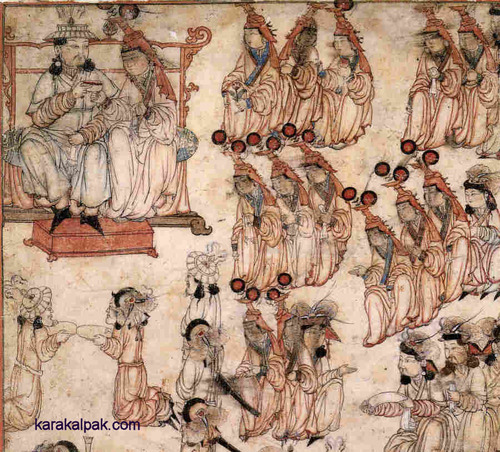

early 14th century Mongol enthronement scene from Iran. Illustration from the Heinrich von Diez Albums, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

We know that at least one boghtaq was brought back to Europe by Marco Polo at the end of the 13th century. It is possible that these headdresses may have been responsible for the sudden popularity of conical hats and headwear across northern Europe in the 15th century, including the conical headdress and veil known as the hennin, which was introduced by Isabeau de Bavière and was worn with the hairline plucked so that no hair was revealed. The hennin has since become the headdress of the Western fairytale princess.

Following Timur’s destruction of the Golden Horde in 1395, the centre of Central Asian wealth and power moved from the Volga to Transoxiana, the former ulus of Chagatay. When Ruy González de Clavijo visited Timur in Samarkand in 1403, Timur was 70-years-old. By then the tradition of the boghtaq had reached ridiculous new heights. Clavijo described the arrival of Timur’s senior wife into the Great Pavilion:

As for the wives of the traders and commonality, I have seen them, when one of them would be in a wagon, being drawn by horses, and in attendance of her three or four girls to carry her train, wearing on her head a boghtaq, a conical headdress decorated with precious stones and surmounted by peacock feathers. The windows of the tent would be open and her face would be visible, for the women folk of the Turks do not veil themselves. One such woman will come [to the bazaar] in this style, accompanied by her male slaves…”

“The Great Khanum wore before her face a thin white veil, and the rest of her headdress was very like the crest of a helmet, such as we men wear in jousting in the tilt yard: but this crest of hers was of red stuff and its border hung down in part over her shoulders. In the back part this crest was very lofty and it was ornamented with many great round pearls all of good orient, also with precious stones such as balas rubies and turquoises, the same very finely set. The hem of this head covering showed gold thread embroidery, and set around it she wore a very beautiful garland of pure gold ornamented with great pearls and gems. Further the summit of this crest just described was erected upon a framework which displayed three large balas rubies each about two fingers breadths across, and these were clear in colour and glittered in the light, while over all rose a long white plume to the height of an ell, the feathers thereof hanging down so that some almost hid the face coming to below the eyes. This plume was braced together by gold wire, while at the summit appeared a white knot of feathers garnished with pearls and precious stones. As she came forward this mighty head-gear waved backwards and forwards, and the Princess was wearing her hair all loose, hanging down over her shoulders. … To keep the crest and other adornments steady on her head the Princess was attended by many dames who walked beside her, some of whom while supporting her kept their hands up to the headdress; indeed in all she appeared to have around her as many as three hundred attendants.”

The Great Khanum was followed by eight more Princesses all similarly robed and bejewelled. This fashion was clearly of Mongol origin – when Ch’ang Ch’un was in Samarkand in 1222 he noted that the wives of chieftains or the wealthy wore a black or dark red turban sometimes embroidered with flowers and other motifs.

In summation, these amazing headdresses have been worn by women of color for thousands of years, but most saliently became equated with white Europeans women through careful revision of history. All too often, the people of Mongolia are associated with dehumanizing “barbarian horde” stereotypes, which grow more exaggerated and outrageous year to year; modern novelizations and fictionalized account become ever more xenophobic and farfetched.

The true history of Mongolia, especially Mongolian women, their history and accomplishments, recede farther away from us and are pushed backwards by the tenets of white western radical feminism, Western Sociology, and beastly pop culture caricatures.

I highly recommend the following reading for more on the amazing history behind the Mongolian Empire.

2 comments:

2/20/16 Thoroughly enjoyed your site...came across it while trying very hard to identify a headpiece on a male possible warrior on an old print that I have...unfortunately it still remains a mystery altho it is what I believe is cone shape.

Again, found your site fascinating.

Lynn Miner,Belmont,Maine

The Smithonian retracted their article's false information and stated that there was no historical proof that Europeans were inspired by Mongolians.

Post a Comment