Source: Tengrinews.kz

15.01.2014

Hal Fosterex-Los Angeles Times journalist, journalism professor

Hal Fosterex-Los Angeles Times journalist, journalism professor

Anyone who has seen a reproduction of the glittering armor of Kazakhstan's Golden Man has marveled at its intracacy – the thinness of the foil and the hundreds of individual pieces in it.

Almaty's Krym Altynbekov has made copies of the Golden Man for several museums in the country during a 40-year career preserving and copying archaelogical treasures in Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine.

Kazakhstan antiquity has also played a key role in his other profession: jewelry making. Designs on 2,000- to 3,000-year-old relics he's studied have inspired many of his creations.

Krym's 30-year-old twins Dana and Elina also restore and reconstruct ancient treasures at the family's 15-person laboratory. His wife Saida helps with preservation and historical-achive searches and keeps records of the restoration work that archaeologists ask Krym to do.

So helping to preserve Kazakhstan's past is truly a family affair for the Altynbekovs.

Master restorer Krym Altynbekov with twin daughters Dana, left, and Elina. ©Vitaly Murashkin

Krym's path toward a preservation and jewelry career began when he displayed a flair for craft-making in school.

“For me it was easy – and people started to ask me to make jewelry and other things for them,” he said. They also asked him to restore arts and crafts items.

His love of creating and restoring what he calls applied art led him to enroll in the Soviet Research Institute for Archaelogical Restoration in Moscow.

One of the first restoration projects he worked on was an important one – the Tsar Village in Leningrad, which has since assumed it original name of St. Petersburg.

In this team effort “we had our own workshop where we made reproductions of ornamentation,” Krym said.

He also helped restore archaelogical or cultural treasures in Moscow, Yekaterinburg and Odessa.

Archaeologists found Kazakhstan's most celebrated historical treasure, the Golden Man, near Issyk in 1969. The name came from the gold battle raiment of the young nobleman.

Krym wasn't involved in preserving the original, which is in the Museum of Gold in Astana, or making the first copy.

But he saw both – and he knew the copy, while good, wasn't a 100 percent replication of the original.

“So in the 1990s my father decided to make his own version,” his daughter Dana said.

He did a lot of research before creating it, combing through books and archives, looking at photos of the original and “talking to the archaeologists who took part in the discovery,” she said.

The result was that the “archaeologists who worked on the Golden Man said my father's version was truest to the original,” Dana said.

Copies that Krym made are now displayed in the Golden Museum, the Museum of the First President in Astana, the Nazarbayev Center in Astana, the United Nations headquarters in New York and other places.

One of Krym Altynbekov's recreations of the famed Golden Man. Photo courtesy of Krym Altynbekov

Preserving a treasure is painstaking, Dana said.

Take the example of a gilded saddle found in 1999 that the Altynbekovs restored and made a copy of.

Archaeologists discovered it in a burial ground at Berel in the Altai Mountains of eastern Kazakhstan, a place where many historical treasures have been found. To insure the best preservation effort possible, Krym arranged for the entire chunk of earth containing the saddle to be transported to his laboratory. The chunk also contained the skeleton of the horse that had been wearing the saddle.

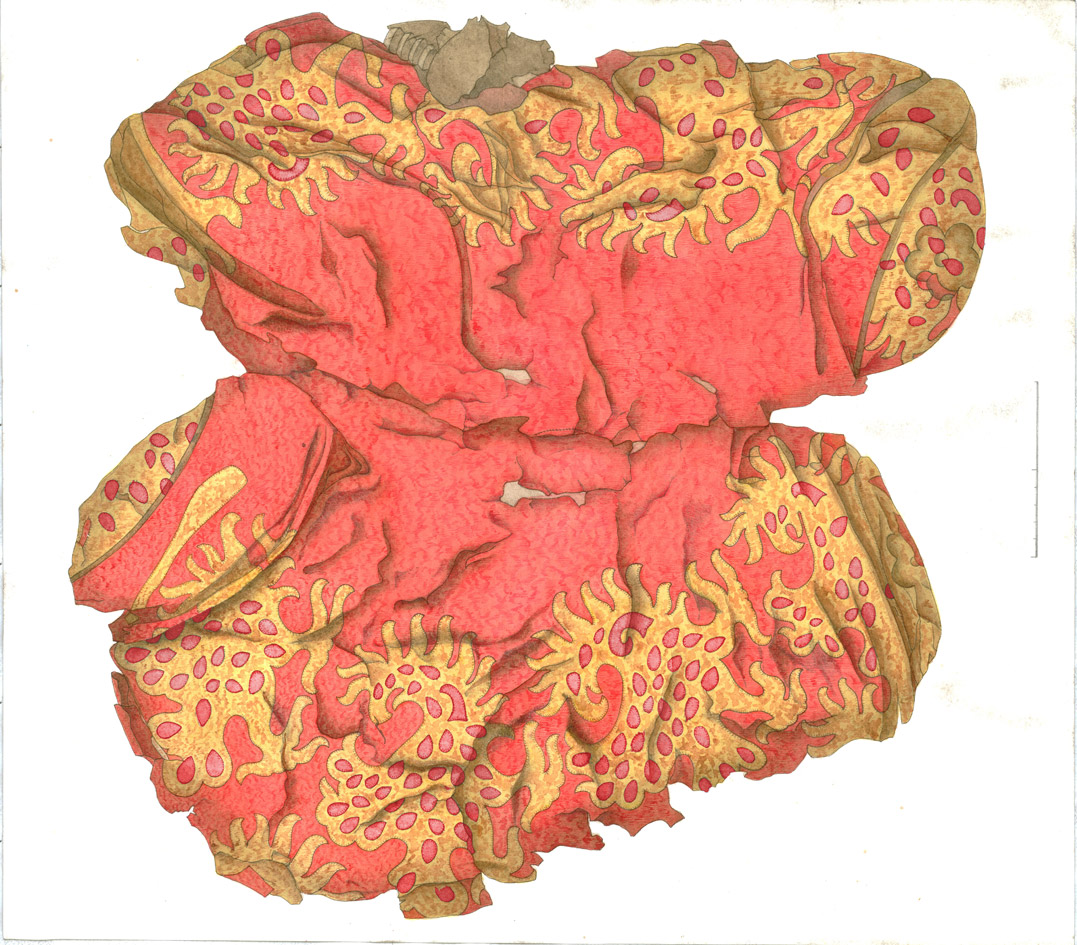

This is a reconstruction of the same ancient saddle that the Altynbekovs created for a museum. Photo courtesy of Krym Altynbekov

They could see that the wood, leather and cloth saddle contained depictions of a tiger attacking a deer and a mythological creative with horns like a mountain goat.

They used a microscope to study what kinds of bacteria were on or around the saddle. That's because different bacteria require different anti-bacterial treatments.

It took several years to identify the bacteria and decide how to neutralize them.

The last step was gentle cleaning of the leather and cloth to make the colors brighter.

The excellent preservation job means the original saddle can be stored at room temperature without special precautions for archaelogists and scholars to see.

The reproduction of the saddle that the Altynbekovs made is stunning. Its rich red color and luxurious ornamentation indicate it belonged to someone of stature.

This is what an ancient saddle looks like after the Altynbekovs restored it. Photo courtesy of Krym Altynbekov

The Altynbekovs have become so renowned at restoration and reproduction that many of the artifacts they've preserved or replicated have been shown in exhibitions abroad. An important one was “Nomads and Networks” at New York University's Institute for the Study of the Ancient World.

Other countries where they've either exhibited or accepted invitations to exhibit include Great Britain, China, Astria, Belgium, Norway, Hungary and Turkey .

They've also given short courses on preservation and reproduction to international scholars and other experts at their Almaty facility.

The laboratory focuses on preservation but includes space for Krym's jewelry work as well.

The 15 lab employees are an eclectic mix – chemists, physicists, restorers, artists, designers and jewelers.

An important new project the Altynbekovs are working on is preserving the garb of a princess whose body was found in 2013 at Urdzhar, near Taldykorgan in southeastern Kazakhstan.

“Our father helped take it from the ground with all the earth around it, and we're working on it now,” Dana said.

Preliminary findings are intriguing.

“The find didn't include a lot of gold, but she had a very interesting headdress – very high, with interesting detail.”

The Altynbekovs also are working on what archaelogists call the Golden Shaman, a woman warrior/priest found in a burial mound in western Kazakhstan in 2012.

“She had some very interesting things with her,” Dana said. “People will be able to see what she looked like – her clothes, her armor.”

A lot of mystery surrounds the woman – “who she was, what clan she belonged to, what regions she communicated with,” Dana added.

Dana said preserving an archaeological find takes a long time – months or even years.

Although the public gets most excited about finds with gold or other valuables, Dana's sister Elina said “gold isn't the treasure for us – it's the information we obtain about our past.”

She said this information can come from wood, textiles and other materials as well as gold.

Trying to create a picture of a civilization from bits and pieces “is like doing detective work,” she said.

“We can use this to understand how our ancestors lived. Their artifacts show us their way of life, their myths, their connections with other civilizations.”

Krym has become one of Kazakhstan's master jewelry makers as well as one of its master restorers.

He's taken most of his inspiration from designs of the Saka or Scythian civilization that flourished in Kazakhstan from the Eighth Century BC to the Third Century AD.

Those designs are simple yet sophisticated. Krym used a design of a wolf with its body rolled up to make a stunning gold tie clasp. Many of his other creations feature animal designs as well – deer and tigers, for example.

The lines of the designs are bold, clean and symmetrical.

.jpg)

Kyrm Altynbekov shows President Nursultan Nazarbayev his family's reconstruction of the garb of a Saka warrior. Photo courtesy of Krym Altynbekov

Krym contends that Sakka art is the foundation of all Kazakh art – the “sunrise” of the genre.

His jewelry creations are superb partly because he's a perfectionist. He sometimes spends months getting a piece just right.

That devotion means his creations fetch high prices.

The typical buyer is a “wealthy man who will be giving the piece to someone as a present,” Krym said.

A testament to his skill is that all of his clients come to him, learning about him by word of mouth. "I don't look for them,” he said. “I don't do any advertising. I just sit in my laboratory doing my work.”

Recently he made several pendants, pins and other items for a children's jewelry show in Astana.

He usually makes pieces one at a time, not in bunches.

He made an exception for the Astana event because he thought “the pieces would help children understand and pay attention to their history and culture.”

Whether it's restoring archaeological treasures or creating contemporary jewelry, the Altynbekovs have always put conveying the story of their country's heritage ahead of everything else.

That's why the family is as much a national treasure as the priceless antiquities they bring back to life

For a VIDEO, click HERE and scroll till the end!

For more information see:http://en.tengrinews.kz/opinion/448/

Use of the Tengrinews English materials must be accompanied by a hyperlink t

For more information see:http://en.tengrinews.kz/opinion/448/

Use of the Tengrinews English materials must be accompanied by a hyperlink t

For more information see:http://en.tengrinews.kz/opinion/448/

Use of the Tengrinews English materials must be accompanied by a hyperlink to en.Tengrinews.kz

No comments:

Post a Comment