‘They’re all wrong’: 86-year-old explorer leads new hunt for Genghis Khan’s tomb on ‘Mountain X’

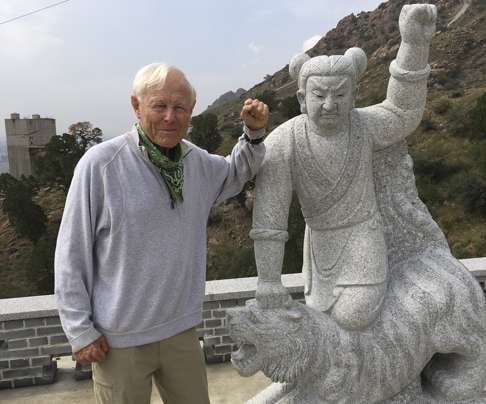

With advancing technology, the race to find the burial place of the Mongolian conqueror is gaining momentum. Former Explorers Club president Alan Nichols is leading a new hunt for Khan’s tomb at a place he calls Mountain X

For nearly 800 years, archaeologists, treasure hunters, scientists, and explorers have been searching for the tomb of 13th century Mongolian emperor Genghis Khan. Many have dedicated their lives to the search, and yet no one has found him.

The problem is, according to 86-year-old American explorer, author and lawyer Alan Nichols, they’re all looking in the wrong place.

A former president of the New York-based Explorers Club, Nichols, who led nine of its flag expeditions – those intended to further the cause of exploration and field science – is an expert in sacred mountains and was the first person to cycle the entire Silk Road from Turkey to China.

Most previous efforts to find the resting place of the founder of the Mongol empire have concentrated on Burkhan Khaldun, a sacred mountain in the Khentii province of northeastern Mongolia. Khan is believed to have been born near the mountain, which is thought to have served as a spiritual refuge for him.

“That’s where all the modern guys are,” says Nichols. “[National Geographic adventurer] Albert Lin is up there, [archaeologist Maury] Kravitz was there, the Japanese and a whole bunch of smaller searches. They’re all wrong.”

Nichols is confident he has nailed down the location of the burial site, which he refers to as “Mountain X” for reasons of confidentiality. “For now, all I can say is that it’s somewhere within the historical Mongol empire, though the borders of China and Mongolia in those days were non-existent, since he had conquered northern China,” he says.

The search has been gaining momentum, thanks to new technology and easier air travel. Lin, a research scientist at University of California, San Diego has been leading an international crowdsourcing effort to search for the tomb using non-invasive technology such as satellite-based remote sensing, asking people around the world to tag anomalies on images taken from space, which could indicate man-made structures under the ground.

“That’s big money and big manpower,” says Nichols. “Albert Lin, he’s a great guy, he has a lab [that’s] darn near half a block. It’s one huge lab with maybe 10 or 12 graduate students – and he is developing drones, satellite imagery, caves and all this wonderful stuff.

“So I love to tell him, God that’s the most impressive stuff I’ve ever seen. The only problem is, you’re 1,000 miles away.”

When we speak via video conference, Nichols is about to set off on a flag-bearing expedition to locate the tomb, taking with him a team of experts and the latest underground testing equipment to prove it.

He has been researching and preparing for this trip for the past 10 years, and his theory is based on a set of necessary criteria he has developed for locating the site.

One of the main reasons he’s convinced the burial site is not in the Khentii Mountains is that the Great Khan – who, he claims, was actually called Chinggis Qa’an – was a master of deception.

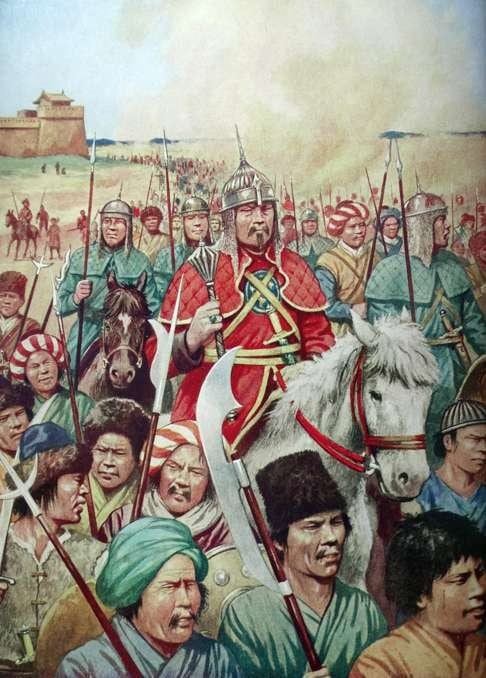

According to Jack Weatherford, author of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World (2004), one of his most successful war strategies was the “Dog Fight”, whereby his armies would fool his enemies into thinking they were retreating, lure them away from their villages, then surprise them with an attack when they were tired, weak and dispersed.

Nichols says: “He was a genius at deception; you don’t think he’s going to use it? And being as wonderful as he is, he’s managed to deceive all these fabulously smart people – including Marco Polo.”

Whether measured by the number of people defeated, countries annexed or total area occupied, Khan conquered more than twice as much as any other man in history, according to Weatherford. Many differing legends surround the burial of Khan, who died in 1227, in Western Xia (in today’s northwestern China) in his mid-60s. There are different stories about how he died; some say he was killed in action, others suspect it was from a wound, and one rumour spread by his detractors even suggested that a captured Tangut queen inserted a contraption into her vagina that ripped his sexual organs, causing him to bleed to death.

According to popular belief, a cortege of soldiers escorted the body back to Mongolia for a secret burial, killing every person and animal they met along the way. Eight hundred horsemen then trampled the area to obscure its location, and then they too were killed so they couldn’t reveal the grave’s location, as were the soldiers who killed them – and the soldiers who killed them.

“It’s not possible that it’s in the Khentii because Chinggis Qa’an and his family made a big deal out of taking a casket up there,” says Nichols. “It’s the first place that everybody would think of. ”

The Mongols believe a body should not be disturbed. Every warrior had a spirit banner, made by tying strands of hair from a warrior’s best stallions to his spear, and that’s where the spirit went when they died. “Dying? That’s something the Mongolians didn’t even think about. You transisted; you changed states.”

Many people have claimed to know the location of Genghis Khan’s tomb, but none have been able to prove it. One website reported a couple of years ago that construction workers in Khentii had stumbled upon the royal burial site. However, another article says they’ve found proof that Jesus was an alcoholic.

Nichols is well aware that the Mongolians want the body to be left in peace. He says his fellow researchers there have told him they hope he doesn’t find it; they don’t want anybody to find it, let alone a foreigner.

“So, why would we look for him? We know Genghis Khan didn’t want it, and I have absolute respect for him,” says Nichols. “The answer is this: I have a list, and there’s at least 70 separate important things on that list that I can find about Genghis Khan and his people from what I know is in his tomb. I can tell you about his religion, his clothes, his nutrition, his war strategy, and of course race – where the Mongols came from. So it gives you unbelievable information.”

The second reason, he adds, is that if he doesn’t find him, somebody else will, and part of his objective is to protect and conserve the site. “The fact is, everybody who’s looking for him has got some axe to grind: you want to find him to get all the glory? Because you want the gold and silver? Or because you’re a professor and you want to be a big hero in the academic world?”

Nichols has been to the site three times and has already detected anomalies. This time he’s returning armed with the latest non-invasive equipment: an advanced form of magnetometer and ground piercing radars. Among the pieces of proof he’s looking for are a silver casket, horses, bones, gold and silver, weapons and siege machinery.

“Let’s say I’m wrong. Let’s say I get under there and I find sheep bones. But – and this is true of all science – the guy who finds the cure for cancer, or immunisation for this or that, he’s dependent on all the other brilliant guys who tried something else and were wrong. I don’t have to bother with Burkhan Khaldun, because Lin’s up there, and he’s as sophisticated as you can get.

“And will I take a chance? I’m not insane – it could be a failure, you always have to face that chance. But if I don’t find it, hopefully somebody is going to find it in my lifetime. Or maybe not. This Chinggis Qa’an was a really creative guy.”

To be continued: the South China Morning Post will be following Alan Nichols’ expedition closely, and providing updates on his progress.

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as:

No bone unturned

No comments:

Post a Comment