Coverage of the war in Syria is rightly focused on the human cost, but there are cultural casualties too, says Kevin Rushby, who remembers Aleppo's Souk al-Madina, a Unesco world heritage site, which was destroyed by fire earlier this week

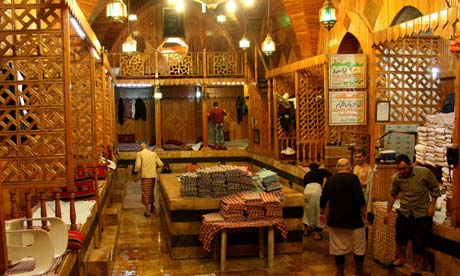

Aleppo souk, Syria Photograph: Kevin Rushby

A few miles from Aleppo are the hills where human beings first domesticated wild grasses. All the wheat we eat originates from those plants and the first farmers. Once those hunter gatherers settled, they set in motion developments that led to towns and then markets. Aleppo was one such place and its souk lay on the first great trade routes, becoming part of an economic engine that made astonishing new products available to more and more people. The warehouses filled up with soaps, silks, spices, precious metals, ceramics and textiles, especially the colourful and diaphanous type favoured by harem-dwellers. Eventually all this mercantile activity focussed into one particular area and a fabulous bazaar was built, mostly in the Ottoman heyday of the 15th and 16th centuries. It was a honeycomb of surprises and flavours, a tribute to the best aspects of human society, but now it has run smack into the opposite tendency: war.

Traditional Turkish baths Hammam al-Nahasin in Aleppo souk. Photograph: Kevin Rushby

Traditional Turkish baths Hammam al-Nahasin in Aleppo souk. Photograph: Kevin Rushby

Of course, the human suffering is far more important and pressing, but I also mourn the loss of a place that so effortlessly encapsulated everything that was light, vivacious, sociable and friendly, everything that war is not. Architecturally the bazaar was not unique. What it had was tradition, heritage and incredible diversity. Five hundred years after Shakespeare made Aleppo souk the epitome of a distant cornucopia, you could still buy almost anything here, eat and drink a vast range of dishes, and even bathe in the traditional Hammam Nahasin. There were eight miles of lanes linking a range of khans or caravanserai – the British Consul held court in one of them well into the 20th century. When I first wandered in via the gate near the citadel, I discovered that there was only one thing I could not find in there: the desire to leave. It was just too diverting and fascinating. Every shopkeeper seemed to want to have a chat over a glass of red tea.

"Let me tell you about scarves. You buy antelope hair for the woman you want and silk for the mistress.'

"What about wives?"

He shrugs. "We have polyester. It comes with divorce papers."

It was clear that this was not a place that ever stood still. Neither was it a museum, and certainly not a pastiche preserved for tourists. One vendor explained that his shop had not been in the family very long: "We got it when the Jews left."

"1948?"

"No, 1908."

I checked later and discovered that many Jews, having come to Aleppo from Spain in the 15th century, then left for America at the turn of the 20th century to avoid conscription into the Ottoman army. Other communities had come when they lost out elsewhere. Many of Aleppo's Christians had come from Turkish cities like Urfa in 1923, bringing with them priceless collections of ancient documents, now also threatened. Ringed around the souk were the churches and mosques of a baffling array of sects and ethnicities, but they all shopped together in apparent harmony.

In great trading cities filled with communal diversity, the inhabitants usually learn to get along and trust each other. It is outsiders who bring danger and suspicion. In fact Aleppo has been sacked, destroyed and left in ruins many times over. When Tamerlane visited in 1400, he left a pile of severed heads outside – reportedly 20,000 of them. The Byzantines had previously done their worst, as had the Mongols, more than once. But it was politics that did for the city's pre-eminence as a market. Slowly and inexorably it was cut off from its hinterlands. The Silk Road died, the Suez Canal was dug, the northern territories were taken by Turkey as were the ports of the Levant. The machinations of the Great Powers turned a vibrant trading city into a divided backwater.

In some ways that decline helped preserve the medieval nature of the place, but now it is gone. When Syria rises out of the chaos, there can be some idea of restoration. But any future attempt to rebuild will always be a re-creation, probably with the tourist buck in mind. That will be better than nothing, of course, but it cannot hide the fact that one of the world's greatest treasures has been lost.

10 CULTURAL TREASURES LOST IN THE LAST DECADE

The Citadel of Aleppo, Syria

As well as Souk al-Medina, the city's citadel was shelled by government artillery. A medieval fortress built on top of several previous structures, it contains a 5,000-year-old temple that was only discovered in 2009. Fighting is said to have destroyed the medieval iron gates.

The ruins of Apamea city, Syria

Built by the inheritors of Alexander the Great's empire, Apamea in north-west Syria has suffered badly with damage from fighting followed by looting. Thieves reportedly drilled two metres to strip priceless mosaics out of the floor and walls.

Krak des Chevaliers, Syria

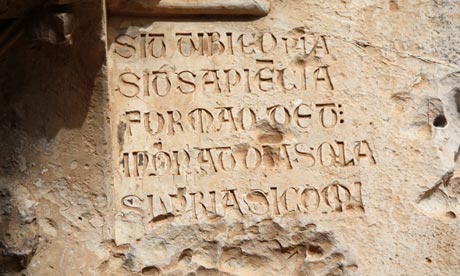

Crusader graffiti in Krak des Chevaliers church. Photograph: Kevin Rushby

Crusader graffiti in Krak des Chevaliers church. Photograph: Kevin Rushby

This supreme example of Crusader military architecture is one of Syria's big visitor attractions. Artillery fire and fighting has apparently been followed by looting. The church with its unique 12th-century Crusader graffiti has reportedly been damaged.

The Dead Cities, Syria

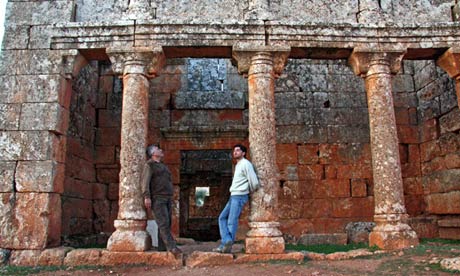

Syrian tourists at Serjilla, one of around 700 Byzantine dead cities, now the scene of fighting. Photograph: Kevin Rushby

Syrian tourists at Serjilla, one of around 700 Byzantine dead cities, now the scene of fighting. Photograph: Kevin Rushby

Scattered around Aleppo are up to 700 ruined cities dating from the first to eighth centuries AD. Evocative and abandoned they are a unique record of life in ancient times. They have also become a battlefield and heavy damage has been reported.

National Museum and Library, Baghdad, Iraq

National Museum, Iraq. Photograph: Ali Abbas/EPA

National Museum, Iraq. Photograph: Ali Abbas/EPA

Home to more than 40,000 ancient documents, the National Library was burned down in April 2003. The National Museum was looted and destroyed a few days earlier while American soldiers looked on. Statues and artefacts, many of them enormous, were lost. About 5,000 documented lost pieces have since been returned or recovered, including the 5,000-year-old alabaster Warka Vase. The priceless collection of 4,800 seals is still missing.

Mosul Museum, Iraq

In the north of Iraq, Mosul's great collection of art and antiquities was also looted. Assyrian, Sumerian and Parthian treasures were taken, and many objects were broken and destroyed in the process.

The minaret of Malwiya, Samarra

The minaret of Malwiya, Samarra, Iraq. Photograph: Nico Tondini/Robert Harding World Imagery/Corbis

The minaret of Malwiya, Samarra, Iraq. Photograph: Nico Tondini/Robert Harding World Imagery/Corbis

One of Iraq's great architectural treasures, the 9th-century spiral minaret was allegedly used by US forces as a sniper post resulting in a bomb blast by insurgents during 2005 which damaged the top of the minaret.

Islamic shrines, Timbuktu, Mali

A still from a video shows Islamist militants destroying an ancient shrine in Timbuktu. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

A still from a video shows Islamist militants destroying an ancient shrine in Timbuktu. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

In actions reminiscent of Cromwell's troops' attacks on decoration in churches, hardline Islamists have reduced some of Timbuktu's medieval Sufi shrines to rubble. Recent efforts to catalogue and preserve the city's treasury of documents are in jeopardy.

Afghanistan

Antiquities continue to be lost with important inscriptions and carvings disappearing. A Buddhist monastery outside Kabul is the latest to be threatened with destruction, this time not by war but by a copper mining company.

Libya

Encouragingly, Libya seems to have got off lightly during its recent conflict though reports of damage to Islamic shrines are now appearing as hardliners try to stamp out "idolatry". A cache of 8,000 antique coins and jewelery was looted from a Banghazi bank and later sold in the city's souks.

No comments:

Post a Comment