From the Victoria & Albert Museum website:

Endere, Miran and Miran Fort

Endere

Endere was once an important military post and centre of Buddhist worship on the southern Silk Road. Coins found there indicate that the Chinese controlled the area as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). During the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), Endere fell to the Tibetans and the city was abandoned in the ninth century AD, when the nearby Endere River changed its course. Stein excavated there in 1901 and 1906, locating remains of its great fort and a number of buildings devoted to Buddhist worship. In one shrine he found textile rags and fragments of Buddhist manuscripts deposited at the feet of stucco statuary, possibly as votive offerings. Written in Chinese, Tibetan and Sanskrit and other scripts, they suggested that the shrine had drawn worshippers from far and wide.

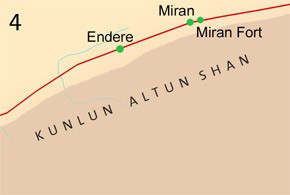

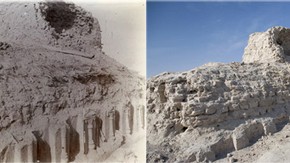

Ruined tower with remains of wind-eroded dwelling in the foreground, Endere, Sir Marc Aurel Stein, 1906. Photo 392/27(104), © The British Library Board (left). Same view, John Falconer, 2008. Photo 1125/16(306), © International Dunhuang Project (right)

Ruins of large building inside Endere fort, Victoria Swift, 2008. Photo 1187/29223, © International Dunhuang Project

The V&A holds on loan a number of textiles from Endere, including tanned leather, wool felts and yarns, woven silk, and braided plant fibres. The intriguing small object (below, left) is made of one length of cream felt which has been folded over and stitched around the edges with cream wool thread. It is unclear what the pad of felted wool would have been used for. Stein discovered it in the ruins of what once was a small dwelling, which he believed dated to the re-settlement after the Tang dynasty effective domination of the Tarim Basin. These fragments of red woollen braid (right) attached with stitching to felted buff wool may have been added decoration to the front opening of a felted garment.

Miran

Miran lies between Kargilik and lake Lop Nor on thesouthern Silk Road. Stein excavated an ancient fort and remains of a Buddhist sanctuary there in 1907 and uncovered spectacular Buddhist murals in its temples and stupas. These depicted winged figures with garlands; imagery which he identified with the mythology and style of Persia and Greece. The appearance of the signature "Tita" led Stein to conclude that the paintings were the work of an artist from the eastern Mediterranean. Temple sculpture, including a colossal Buddha head, was rendered in the opulent Gandharan style of northwest India. Stein called this fusion of regional styles Graeco-Buddhist and determined that the site had flourished in the first centuries of the millennium, when trade along the southern Silk Road had thrived.

View looking along base of stupa, Miran, Sir Marc Aurel Stein, 1906. Photo 392/27(118), © The British Library Board (left). Same view, Victoria Swift, 2008. Photo 1187/2(131), © International Dunhuang Project (right)

The V&A holds on loan from Miran, silk and wool fragments, and a group of lotus flowers made of cotton and silk and plaster-covered fabric fragments. These artificial flowers (below, left) were cut out flat from plain woven cotton and silk, some dyed blue and some red while others were left undyed. The flowers were cleverly made up with wooden pegs and tufts of silk thread to represent stalks and stamens. The stalks would then have been pushed through a painted cloth which perhaps covered the floor, walls or even the ceiling. The flowers may have been votive offerings of the worshippers at the shrine of Miran. The remains of a coarse cotton cloth (centre) has been covered with a very thin coat of white plaster painted dark blue. Onto the wet plaster were fixed groups and sprays of artificial leaves cut separately out of red and blue cloth and stuck together. Stein discovered these in the ruins of a shrine, square outside but circular within, which had once been surmounted by a dome and enclosed a small stupa in its centre. Spectacular murals had once decorated the walls such as winged figures and western-looking people in a 'Graeco-Buddhist' style, as coined by Stein. He described the long length of silk (right) as a girdle based on the much worn ends. He found it in the ruins of a small building with just one room and a hemispherical dome above it. It was still rolled-up. The width of the silk is about 6 centimetres wider than the standard measurement of silks made during the Han and Qin dynasties, and therefore might belong to a later date. The so-called girdle was maybe left behind by a traveller several hundred years later seeking shelter when the roof of the building was still intact.

Miran Fort

The Miran fort lies midway along southern Silk Road, at the foot of the Kunlun Mountains. When Tibetan troops occupied the area in the late eight century AD, they built the fort as part of a defensive network in and effort to control the surrounding area, which included a nearby mountain pass into Tibet, and the Qinghai route of the Silk Road into China. The fort was abandoned at the end of the 9th century, and had declined into a small farming community by the time Sir Aurel Stein visited the area.

In 1907, Stein excavated rubbish heaps at the fort and found wood slips, dating from the eight to the ninth century AD, which provided early examples of Tibetan writing. He also found fragments of wool rugs in bright colours and pieces of silk.

Ruined structure, Miran Fort, Sir Marc Aurel Stein, 1914. Photo 392/28(357), © The British Library Board

The V&A holds a large number of textiles from the Miran Fort on loan. They include patterned and plain woven silk and wool, woven and spun hemp, woven horsehair, cords and painted silk.

No comments:

Post a Comment