No, a mysterious Chinese-style palace thousands of miles from home in Siberia.

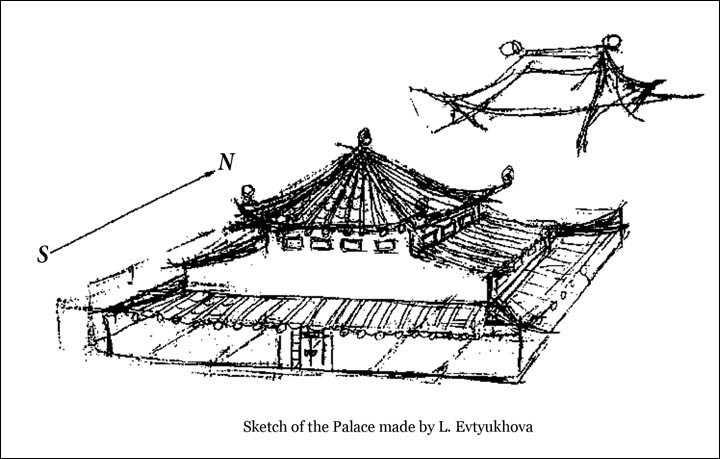

Hidden treasure of Siberia. Picture: L. Evtyukhova

But whose was it, and how did it get here? Was it Han or Hun? Some 74 years after it was unearthed, an academic debate continues as to who built it.

It was in 1940, during the construction of a road from Abakan to Askyz, that workers stumbled across fragments of ancient clay tiles as they excavated a low hill. A local archaeologist Varvara Levashova was quickly on the scene, and her attention immediately fell on hieroglyphic inscriptions on the tiles.

A victim of Stalin-era repression, she conducted her work in the most terrible conditions: in 1937, four years earlier, her husband had been shot as an 'enemy of the state', while her father - who had been a chaplain known to the Tsar's family before the Bolshevik Revolution - was also executed the same year.

Varvara Levashova conducted her work in the most terrible conditions. Picture: O. Sveshnikova

Herself condemned to live with her two young daughters in a basement room measuring eight square metres with no electricity, she nevertheless discovered a unique and stupendous palace.

Suffering from starvation rations she confessed to her archeologist friend Lidia Evtyukhova - who she summoned from Moscow to help with the research: 'I feel I have hardly any strength to go on, like a wretched nag who is about to drop dead in the street'.

Despite these deprivations, Levashova realised that the ruins must have been the scene of a significant building long ago, but the awesome scale of it, some 1,500 square metres, was not immediately evident. The archeological dig began in 1941 but was interrupted by the Second World War, continuing in 1944 and finishing in 1946.

Clay tiles with Chinese stamps and bronze door handle. Pictures: Khakass National History Museum

Levashova and her fellow archeologists unearthed clay walls preserved to a height of 1.8 metres and other remnants of what they realised was a structure of a palatial scale, some 45 metres in length and 35 metres wide. In the central part of the palace was a large hall area of 132 square metres, and around it 20 rooms (in a row on the north and south sides and in two rows on the east and west).

The rooms were connected by doors. The walls of some rooms were very thick, up to two metres, with adobe flooring. Examining it further, the archeologists found heating channels under the flooring, lined on the sides and top with stone slabs.

The occupants plainly knew the importance of staying warm in the harsh Siberian winter and adapted their architecture accordingly. On the floor were found traces of braziers, used for heating the palace rooms. The wooden doors of the palace did not survive, but inside the building were found door handles cast in bronze depicting a large ring in the mouth of a fantastical horned creature.

A few utensils were discovered in the rooms - an iron knife, fragments of clay vessels, some jewellery.

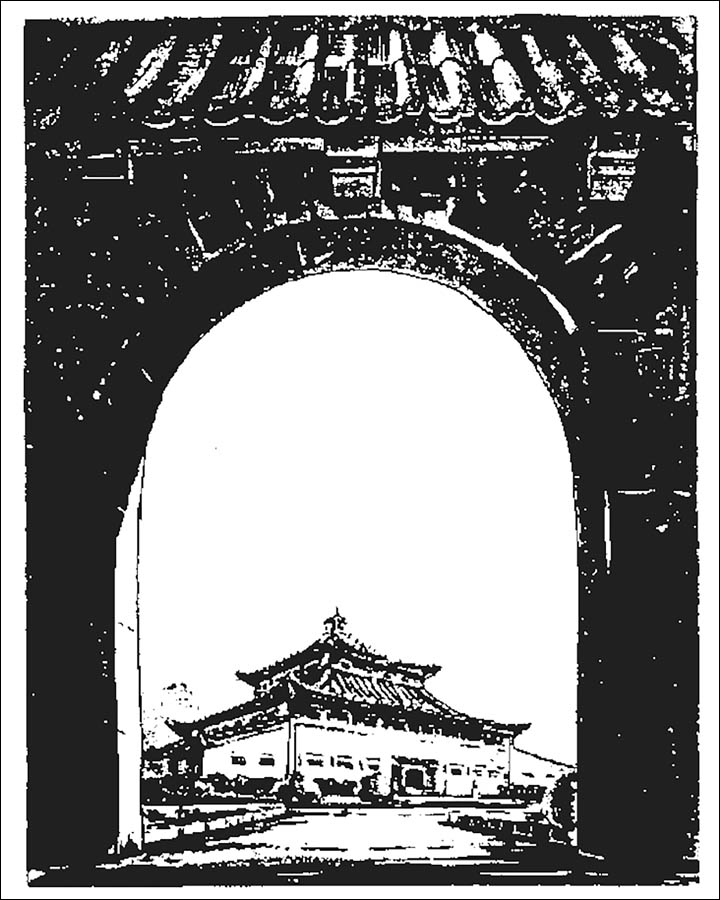

Some 74 years after the palace was unearthed, an academic debate continues as to who built it. Pictures: Panoramio

Recently in recounting the story, the website chinatopix.com rightly suggested the palace the equivalent of a palm tree on Mars, which neatly highlights the incongruity of this Chinese treasure in Siberia.

Sinologist Vasiliy Alekseev in Soviet times had dated the ruins of what is now known as Tashebinsky Palace as being from the second to the first century BC, and drawings were made to highlight its likely look in the landscape of Khakassia. It indeed appeared to be typical of the Han Empire in China - which flourished from 206 BC to 220 AD - and yet it was almost 2,000 kilometres from the known extremities of its borders. Off the beaten track, to put it mildly.

The exotic view emerged in Soviet times that it had been built by Han dynasty's General Li Ling, who was taken prisoner in 99BC after his 30,000-strong forces were massacred by the superior strength of the Xiongnu during an expedition he led for Emperor Wu.

General Li Ling. Picture: xinhuanet.com

Li was initially assumed to have died in the defeat, but it was later clear that he defected and began training the Xiongnu forces in Han battle plans.

So the theory was that this palace near modern-day Abakan was a power base for Li Ling in exile, his home from home, built in traditional Han style while he was on the side of the Xiongnu, seen by some authorities as being Huns.

Later, scientists reassessed this, interpreting the hieroglyphics to suggest that the place dated from slightly later, the first century AD, ruling out Li Ling.

The new hypothesis was that the palace was built for the wife of Hun governor Syui-budan. Her name was Imo: her mother was a Chinese woman and her father a significant Hun warlord and ruler. Yet another version from archeologist Alexey Kovalyov in 2007 saw it as the palace of Han pretender Lu Fang, who declared himself the great-grandson of Emperor Wu and raised a rebellion, supported by the Huns.

In fact the evidence found at the site does not establish which, if any, of the theories is correct.

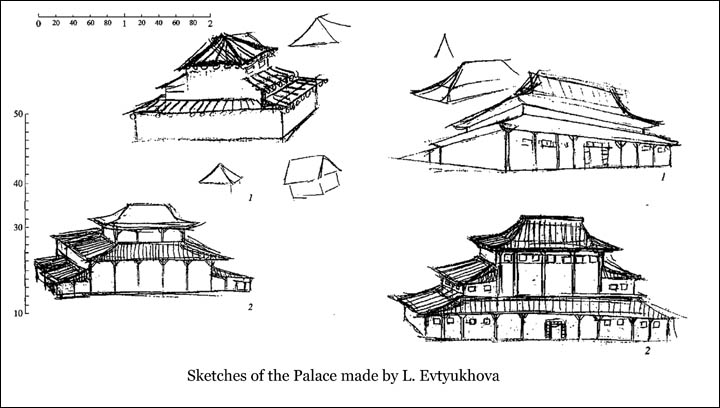

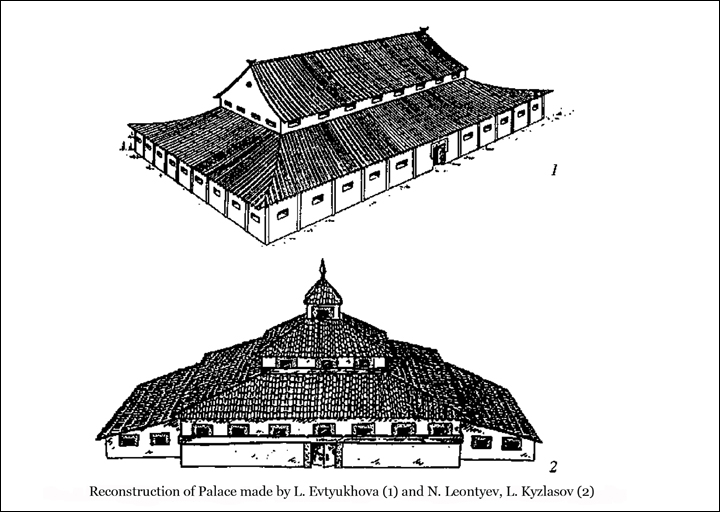

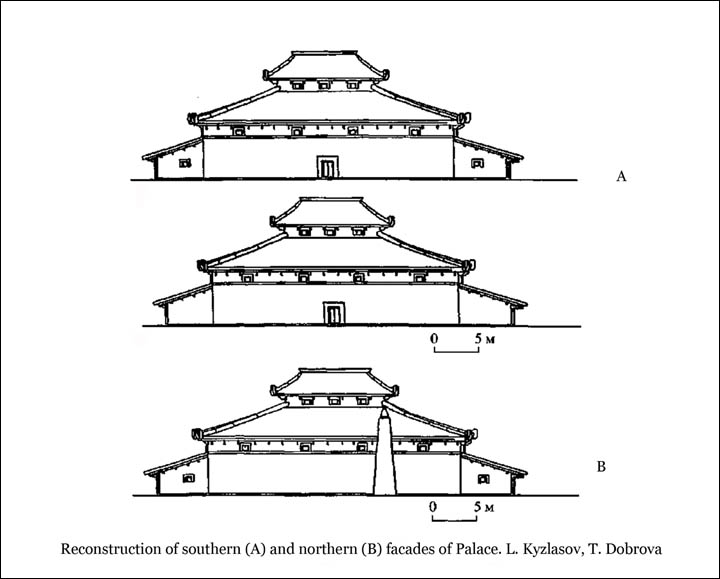

The first reconstructions show a one-story building with a two or three tier roof, in Chinese-style. Pictures: L. Evtyukhova

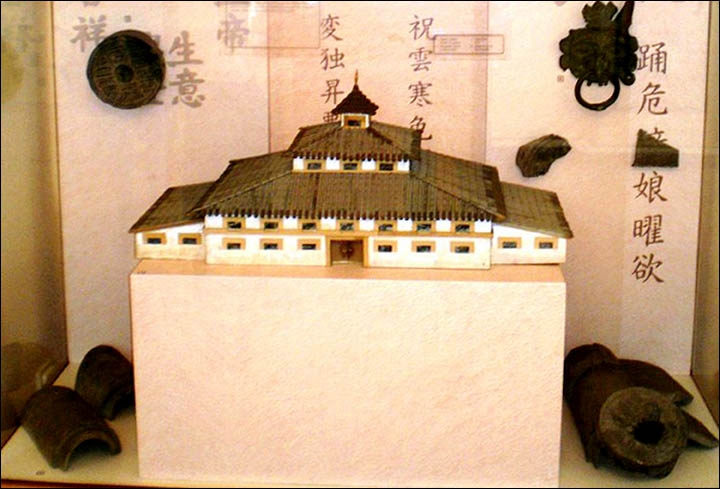

Sadly, today there are no traces of the palace at the place it was built since in the Stalin era the decision was taken to totally excavate it for the sake of the new road. In 2010 there were attempts to build a replica, and a museum, but this did not go ahead. Yet from analysis of the archeological finds, we can imagine how did the palace looked.

The first reconstructions were made in 1945 by Lidia Evtyukhova - the expert summoned by Levashova to the site - and show a one-story building with a two or three tier roof, in Chinese-style.

It should be said that a later review of the evidence by archaeologist Leonid Kyzlasov, in 2001 alleged that the building was built not according Chinese ways - except for the roof tiles - but more in a Central Asian style, postulating it was built and owned by eminent Huns.

First drawings and reconstruction of the palace. Pictures: L. Evtyukhova, L. Kyzlasov, Khakassky National History Museum

The latest reconstruction of the palace made by Kyzlasov is available in Khakassky National Museum of Local History. A question is whether more modern scientific techniques could be applied to the finds from the site, which is in modern-day Abakan, and provide answers that have so far eluded the experts.

If anyone has thoughts on, or knowledge about this Siberian palace, we would be pleased to hear from you.

No comments:

Post a Comment