In his recent book

Global Crisis: War, Climate Change & Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century, Geoffrey Parker states: “although climate change can and does produce human catastrophe, few historians include the weather in their analyses.” This is generally true, and the distance between historians and the weather may not have improved (indeed, may have been underscored) by the evolution of environmental history as a separate branch of historical research. Moreover, while the collection of historical climate data has never been more robust, instances of collaboration between scientists and historians are still very few and far between. In 2006, the National Science Foundation launched a program for research on Coupled Natural and Human Systems, capturing the need to model the interaction between societies and environments. Few of the projects funded so far, however, involve a long-term historical perspective or engage actual historical questions. One of these, funded last year, is titled “Pluvials, Droughts, Energetics, and the

Mongol Empire” and is led by Neil Pederson, Amy Hessl, Nachin Baatarbileg, Kevin Anchukaitis, and myself.

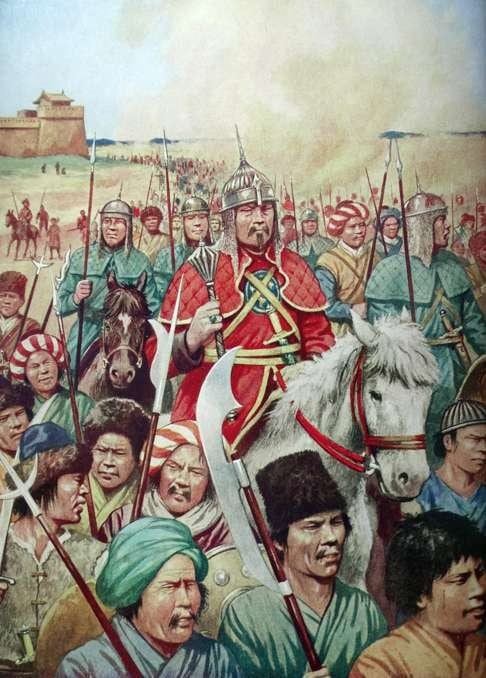

Based on data collected in Mongolia over several years by climate scientists, the project aims to study climate change in relation to a particular set of circumstances, namely, the rise to power of Chinggis (or Genghis) Khan and the beginning of one of the most remarkable events in world history. Everyone knows Chinggis Khan but no one has so far been able to clearly explain the process through which the Mongols became so powerful nor why they would feel compelled to move out of Mongolia and conquer most of the Eurasian landmass. All countries from China to the Black Sea, including Central Asia, Russia, Iran, and parts of the Middle East, came to be under Mongol rule for the best part of the thirteenth and a good portion of the fourteenth centuries. The legacy of Mongol rule, however, continued to be felt in all of these regions well into the modern age. Mongol armies reached even beyond these lands: they invaded Poland, Hungary, and central Europe, riding as far as Vienna. Although the memories they left were not altogether pleasant (the Apocalypse was often invoked as a fitting metaphor), Europeans were intrigued and eventually found grounds to look at the Mongols in a more positive light and try to learn more about them.

The first exploratory contacts were established by Franciscan and Dominican missionaries. They were not necessarily sympathetic to the Mongols, but looked at them in more realistic terms: not as agents of divine wrath, but as a people who were seriously different, and even a little barbaric, but nonetheless human. Ever since their first appearance on the world scene, people wondered about where they came from and how they got there, but academic curiosity about their appearance was soon replaced by more contingent questions about their system of government, religion, habits, and especially the opportunities that their conquest opened to priests and merchants. Popes and European kings were intrigued by the blows dealt by the Mongols to their bitter enemy, the Saracens. Marco Polo and other travelers rendered an otherworldly Catay and the Mongols who ruled it familiar to a wide European public. Trade followed the scriptures and eventually a copy of Marco Polo’s book, still preserved, was attentively read, glossed, and annotated by Christopher Columbus prior to his fateful journey.

The reason why the rise of the Mongols, and their appetite for conquest, has never been explained is simple on the surface: there are no sources that can tell us what happened. Every history book repeats, with greater or lesser accuracy, what we learn from a special Mongol source, the epic saga, orally composed and transmitted sometime in the mid-thirteenth century, known as the Secret History of the Mongols. This marvelous composition retells the story of the rise of Temüjin, raised to be the khan of the Mongols with the title of Chinggis Khan in 1206. Episodes of the life of the Mongol conqueror, from foreordained birth to mysterious death, are narrated in beautiful prose and poetry. The trials and tribulations of Temüjin make it clear that he lived in a time of conflicts and violence. Skills, sagacity, fortune, and perseverance yield their rewards when he is able to unify all the Mongols under a single rule, an accomplishment followed in short succession by the decision to invade first northern China and then central Asia.

The historicity of the epic rise of Chinggis Khan and the credibility of this account have long been doubted, but even if we were to take the Secret History as fully reliable, actual historical questions would be left unanswered. It has been so far impossible to explain how Chinggis Khan mustered the strength to extend his military operations and his rule so far outside his power base, originally located in northern Mongolia. It is also difficult to argue in favor of any compelling reason why, once peace had been restored among the various warring Mongol clans, more campaigns, as far-flung as Samarkand, the Caspian Sea, and the Himalayas, should be undertaken. Should we pin it on pure hubris, or say that Chinggis went on pillaging and conquering “because he could”? The Mongols did not keep historical records of any kind, and no Chinese or any other written sources provide clues that would allow historians to answer more specific questions: how was a central government and a large army supported? What was the economy of Mongolia after thirty years of civil war? How could the Mongol warriors be so successful in mounting large military operations given that the economy and society were supposedly in shambles?

In 1950, Owen Lattimore, the renowned historian of Inner Asia, wrote: “As is now generally known, the Mongol eruption, and others of the same kind, were due to political causes, not to desiccation in Mongolia as was once assumed. Within historic times there have been no climatic changes that permanently reduced the amount of grazing necessary to support the population that seems to have lived in Outer Mongolia up to the present day. At times, sudden droughts, or a series of droughts, must have brought about small migrations from the poorer pastures bordering the desert, but with the return to normal conditions the desiccated areas appear to have soon received a fresh population.”1 Lattimore’s reactions to environmental determinism were credible and justified. The notion that Mongol warriors may have poured out of the steppes because worsening climate, marked by extensive droughts and frosts, might have pushed them to seek, literally, greener pastures, was not endorsed by him. Yet the idea that a climate-induced environmental crisis played some role in the general unfolding of events continued to linger. In a short note published in 1974, Gareth Jenkins presented climate data showing that “a steady and steep decline in the mean temperature in Mongolia in the years 1175–1260” could have had sufficient explanatory power to be included together with other factors, since a decline of such magnitude would have certainly had a “profound impact on a pastoral nomadic economy like in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Mongolia.” Jenkins thus argued that “a major climatic overturn did much to encourage the end to the infighting and vendettas among the Mongol clans and make possible their reorganization under Chinggis’s military authority,” and that “their enthusiasm for the task of conquest may well have been fueled by a climatic defeat at their backs.” Jenkins does seem to imply that the end of the civil wars among Mongols as well as their appetite for conquest could have been reactions to a prolonged worsening of the climate and environmental conditions. Still, climatic causes did not get much traction among scholars of Mongolian history, and historical works have remained essentially agnostic on this point, preferring to stick closely to the story presented in the few written sources, and thus privileging, like Lattimore, a political reading.

Pastoral nomadic societies are extremely sensitive to climate changes. Extreme events, such as heavy snowfalls, frosts in winter, or droughts in summer, can, in a very short time span, affect severely the delicate balance between humans, animals, and land. Even in recent times, especially harsh winters have caused the loss of a large portion of the Mongolian livestock. But how should one relate such potential disasters to historical events? Moreover, what happens when the climate becomes unusually favorable to the production of pastoral resources? Historians have overwhelmingly focused on downturns rather than upswings. Based on tree-ring analysis, climate scientists involved in the project in which I am participating have reconstructed the climate of the Orkhon Valley, located in east-central Mongolia, for more than a thousand years.2 This is the locale where the future capital of the Mongol empire, Karakorum, was going to be built, and an important political site for several nomadic empires such as the Turks (sixth to eighth centuries) and the Uighurs (eighth to ninth centuries).

The data gathered from the tree rings shows an anomaly that caught the eyes of scientists. While the end of the twelfth century (especially the 1180s decade) was marked by prolonged droughts, the period from 1211 to 1225 was instead marked by persistently wet conditions, which would have increased the available pasturage, thus allowing for an increase in livestock. The anomalous sudden transition from a prolonged dry period to a prolonged wet period should indeed create conditions that might have affected the formation of a new political order in Mongolia.

Several studies have attempted, with different degrees of analytical rigor, to link climate change with the emergence of violent conflict. Although such studies are typically based on more-or-less strong correlations, it stands to reason that a reduction of resources may force nomadic groups to move in search of sufficient pasture to feed their animals, thus clashing with other groups over access to grassland. The Secret History of the Mongols describes a bleak world rife with tensions, violence, wars, and poverty. Of course, this could just be a standard literary device to describe a society in disarray, whose salvation would come as it was brought under a novel order by the new leader. This messianic element is necessary to ensure the legitimacy of a new type of sovereignty (supratribal) claimed and constructed by Chinggis Khan. However, surely one cannot exclude that such wars and feuds actually happened. The concomitance between deteriorating climate conditions, tales of violence, and a vast body of literature that tends to link climate and conflict, makes it plausible that Mongolia at the end of the twelfth century was indeed perturbed by winds of war and fierce intertribal conflicts.

Contrary to Jenkins’s hypothesis, there is no reason to believe that conflict would subside and people would place themselves under someone’s rule because of deteriorating climate conditions. The most likely scenario is that during the time of intertribal wars and declining climate, Mongolia experienced vast loss of livestock, displacement of people, and the rise of military commanders vying for scarce resources. The political process common among ancient nomads eventually would remake the political order either by reconstituting territorially based political nuclei (clans and tribes) in a new equilibrium, or fully redefining it by endowing a supreme leader with exceptional powers, leading to a complete overhaul of the political order, one that went from decentralized to centralized, and thus organized in a new hierarchical pyramid-like structure. As we know, the latter is what happened, as all Mongols were brought under a single ruler thanks to the personal skills of Chinggis Khan in forging alliances, isolating his enemies, and introducing new institutions.

Military operations against north China began to take place after Chinggis Khan was raised (literally, on a felt blanket) as the ruler of the people. The climate record for the first ten years of the thirteenth century is variable. The first part of the 1200s decade shows an amelioration of the climate followed by yearly fluctuations and a minor downturn. I would not suggest that Chinggis’s military operations were in any way related to climatic changes, but simply note that this period is surely very different from the previous two decades and especially from the very dry 1180s. However, the military operations of Chinggis Khan expanded exponentially from the 1210s until his death in 1227. During his time, the Mongols launched major expeditions in northern China against the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) and in Central Asia against the Muslim kingdom of the Khwarezmshah. The question that a historian needs to ask when climate data is taken into consideration is: what possible effects could a wetter climate have on the type of political structure and on the military operations initiated by Chinggis Khan?

The most reasonable hypothesis toward which our project is working is that a wetter climate, with an increment of the grassland biomass and increasing levels of energy, could have aided the rise of a more powerful state in several ways. Reasoning hypothetically, we need to consider economic, political, and military aspects. On the economic side, we can infer at least two ways in which a moister climate plays a role. First, it assists the rapid economic recovery of the herds and welfare of the people after many years of privation and uncertainty. Secondly, it is possible that in various locations agriculture may have been stimulated, thus contributing to the net increase of available resources. Finding agriculture in Mongolia in this period would be by no means surprising, given the presence of stable settlements and urban sites at different times in the Mongolian steppes through its history. Some evidence of agriculture has been found in Karakorum when it became the Mongol empire’s capital, under Ögödei Khan. From a political point of view, the increased productivity of the land would allow greater density of people over a given territory. The Mongol court, especially one that concentrated all the power in a single seat, required thousands of servants, soldiers, animals, and, of course, all the families of the ruling elite and aristocracy to be located in a fairly contained area. Even if additional supplies were brought in from the outside, a highly productive area would have guaranteed a steady supply of surplus resources. This particular aspect would also be relevant to military operations, since a considerable number of soldiers, including the imperial bodyguard, would be living in close quarters and under the direct command of Chinggis Khan. Even more important, the Mongol army required a large number of mounts—each soldier would have needed on average five horses—which would not have been available in dry conditions, but would have been plentiful as pasture became more lush and nutritious. These considerations show that the wet environment might have had an important supporting role in fueling military operations and political centralization, sustaining the rapid recovery of the Mongol economy, and creating surpluses critical for the creation of “state-like” institutions and a centralized command structure and administration.

Yet, there are a number of problems and questions that need to be addressed. For instance, the climate data comes from the Orkhon valley, rather than from the Onon valley, in northeastern Mongolia, where Chinggis Khan was based in 1206. There are indications that Chinggis moved the center of his operations to the Orkhon in the late 1210s, and availability of better pasture may have been a reason for this, but we cannot say that for sure until we have more data for other parts of Mongolia, and in particular the Onon-Kerlen region. Another important question is whether the hypothesis that favorable climate and increased rangeland productivity may have played a critical role in the politics of pastoral nomads should be tested against other historical cases. In historical research it is impossible to replicate exactly the same conditions, but our hypothesis would be strengthened if we were to observe that a rapid change from a period of temperature decline and dry weather, followed by markedly better conditions, coincided with drastic political transformations. No systematic research has been attempted so far. Some positive, if not fully relevant, indications, however, can be registered. For instance, Gergana Yancheva, et al., find that Chinese dynasties were established during wet periods, which may indicate a correlation between military operations and energy levels.3 Closer to our time and problem, a study of paleoenvironmental conditions in the territory of the Golden Horde (Russia–Ukraine) finds that “an increase in climatic humidity within this dry region took place in the period of the High Middle Ages, with a peak in the thirteenth–fourteenth centuries” and that “the favorable climatic, vegetation, and soil conditions in the Lower Volga steppes in the thirteenth–fourteenth centuries were factors that affected the local ethnic and socioeconomic conditions: numerous permanent settlements were established in the regions, and some nomads began crop cultivation.”4 The correlation established in these studies between social development and better climate conditions encourages further probing into the role played by a more favorable environment in the history of nomads.

Beyond exploring ways in which climate data can open new avenues to explain otherwise irretrievable historical scenarios, coupling scientific and historical research may also produce models for future projects. This is especially important in the study of the history of people who have not left much in terms of documents or written records. Material culture, archaeological research into settlements and urban sites, palaeobotanical and palynological data, and climate science can provide evidence that, carefully examined in a comprehensive manner, may bring new insights into historical problems that would otherwise remain shrouded in mystery.

Nicola Di Cosmo joined the Institute as Luce Foundation Professor in East Asian Studies in the School of Historical Studies in 2003. His main field of research is the history of the relations between China and Inner Asia from prehistory to the modern period. He is currently working on questions of climate change at the time of the Mongol empire, the political thought of the early Manchus, and commercial relations in northeast Asia on the eve of the Qing conquest.